عمارة القاهرة الإسلامية -

من القرن السابع حتى القرن الثامن عشر

![Tala'i Abu Reziq mosque, elevation and details, 12th century. Little beyond Posse's details, elevation, and plan have survived except "the planks [on which Imam Husayn's body was bathed] embedded above the middle arch of the maqsura [traditionally engraved and ornamented], which have never borne inscriptions."](https://lh6.ggpht.com/-miiDTUZLKXE/TxLTo1ug38I/AAAAAAAAPIY/1AzEoN6hvhY/image013.jpg?imgmax=640)

من القرن السابع حتى القرن الثامن عشر

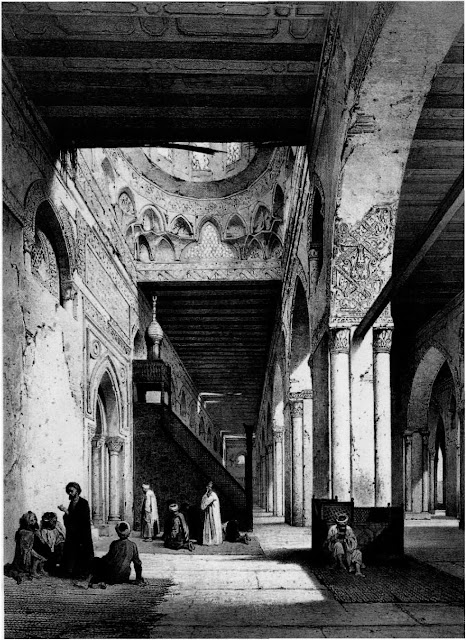

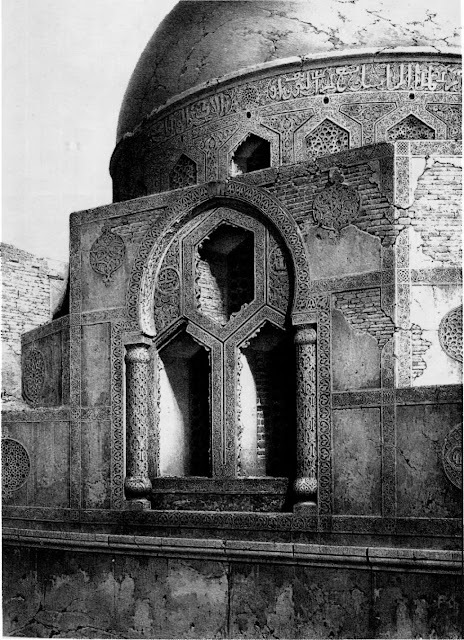

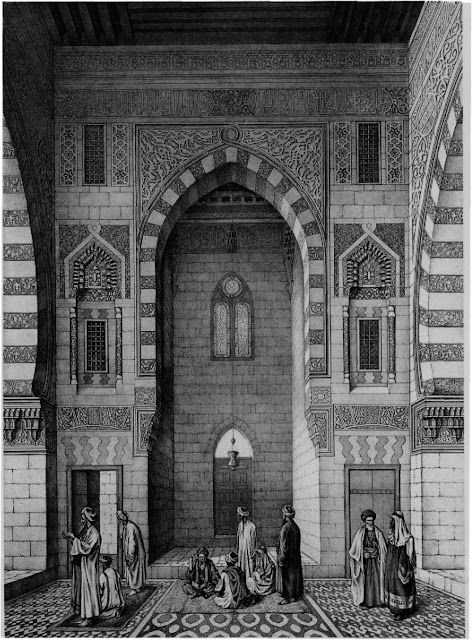

Mosque of Ali mad ibn Tulun,

interior of the maqsura, 9th century. Gypsum and ash pillars accentuate

the domed mihrab. The mosque, inspired by the great mosque of Samarra in

the patron’s homeland, accommodated a burgeoning population of troops.

The decaying ornament in the arch’s soffit no longer exists.

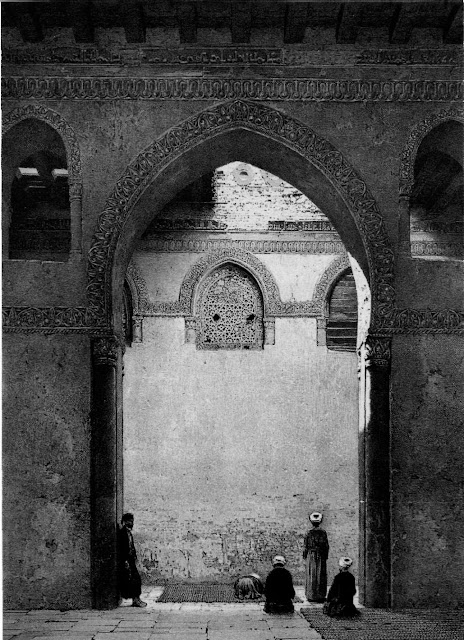

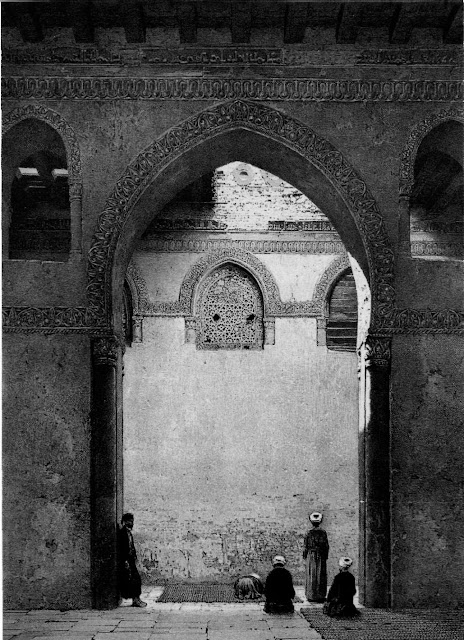

Mosque of Ahmad ibn Tulun,

arcade and interior windows, 9th century. Prostrating men provide scale

and accentuat the arcade’s massiveness. Arches vary Irttle; they rest on

brick pillars with a rectangular plan. Unobstructed interior windows

and laced exterior windows form interesting contrasts, capturing the

movement of air and light.

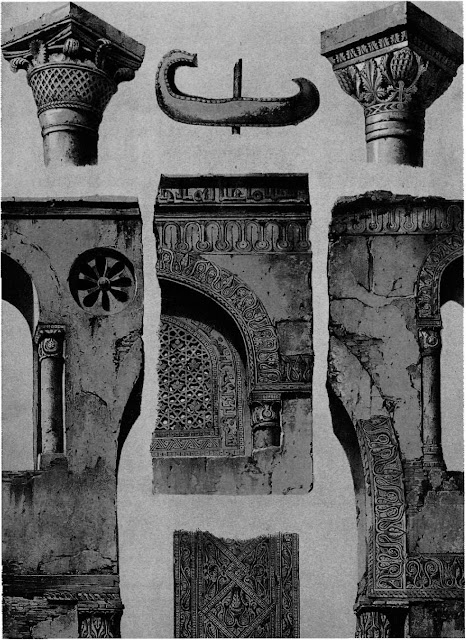

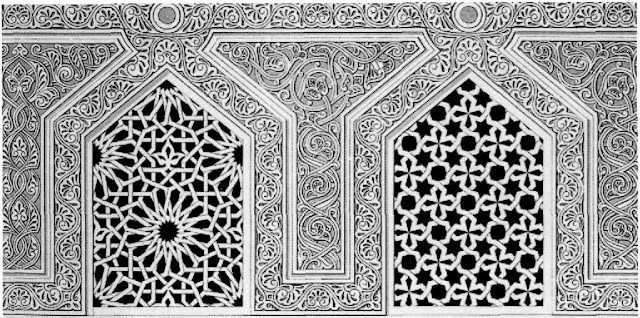

Mosque of Ahmad ibn Tulun,

details, 9th century. Prisse contrasts the interior arched spandrels

with the decorated arches of the courtyard, which display a broad frieze

of stucco rosettes. Stucco- work frames the windows distributed around

the whole building. According to Prisse. these helped disburse

fragrances of ambergris into the congregation.

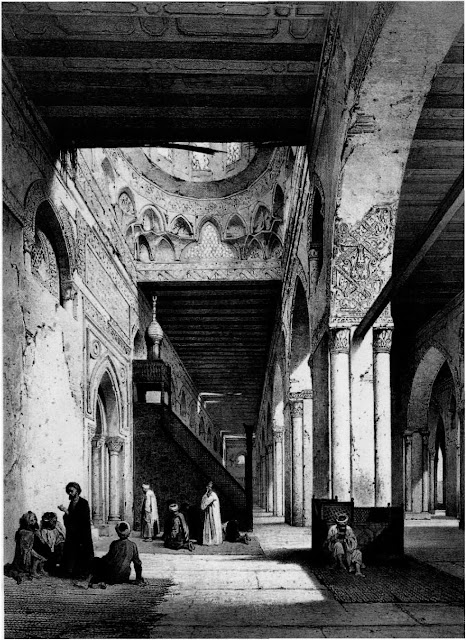

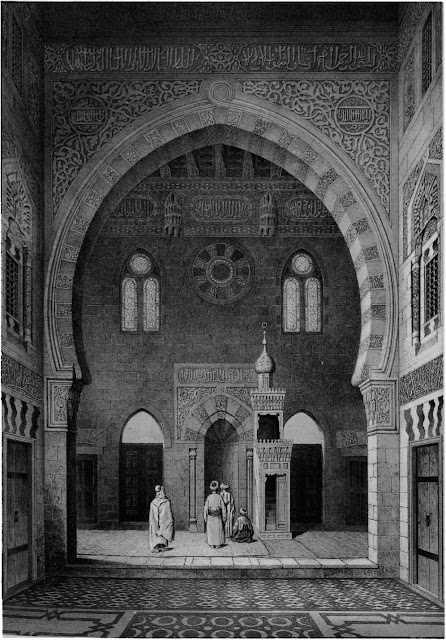

Al-Azhar mosque, main

courtyard, 10th-18th centuries.Students congregate around columns,

highlighting the mosque’s function. Prisse’s focus on the structure as

one adjusted and renovated through various epochs provides insight into

the evolution of Cairo and the position of theological, scholarly

activity in the cityscape.

![Tala'i Abu Reziq mosque, elevation and details, 12th century. Little beyond Posse's details, elevation, and plan have survived except "the planks [on which Imam Husayn's body was bathed] embedded above the middle arch of the maqsura [traditionally engraved and ornamented], which have never borne inscriptions."](https://lh6.ggpht.com/-miiDTUZLKXE/TxLTo1ug38I/AAAAAAAAPIY/1AzEoN6hvhY/image013.jpg?imgmax=640)

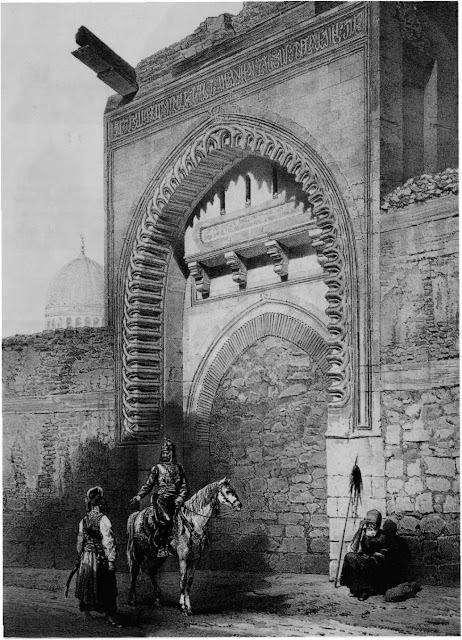

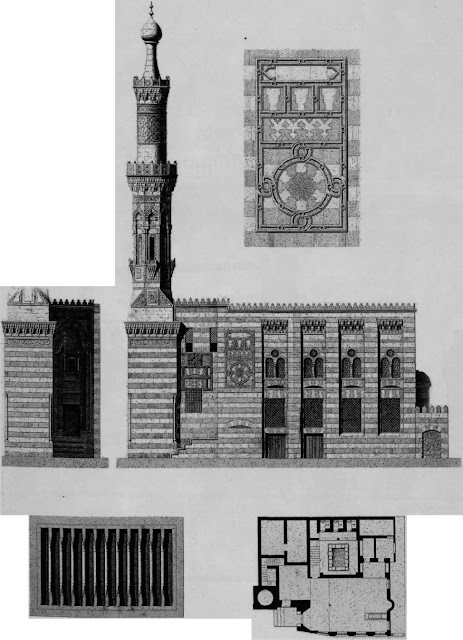

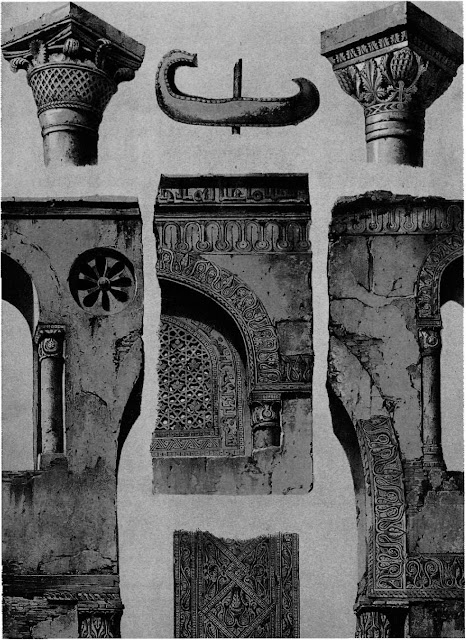

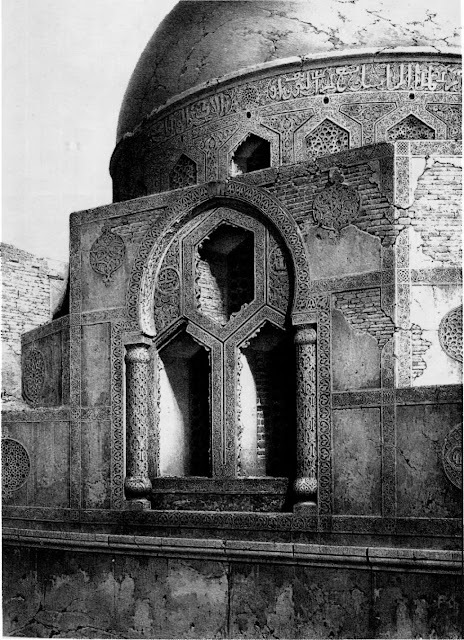

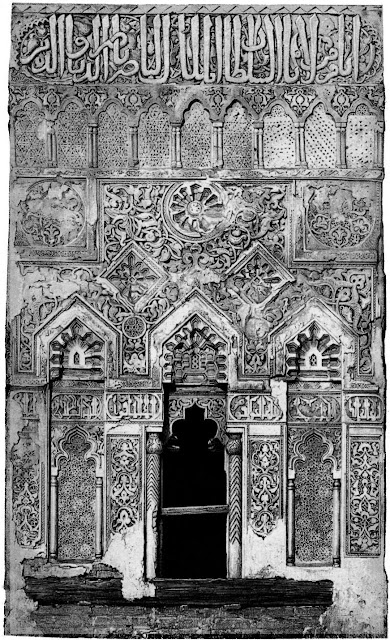

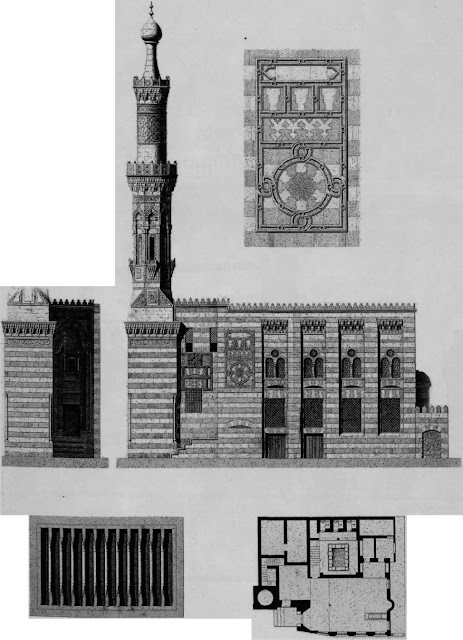

Tala’i Abu Reziq mosque,

elevation and details, 12th century. Little beyond Posse’s details,

elevation, and plan have survived except “the planks [on which Imam

Husayn’s body was bathed] embedded above the middle arch of the maqsura

[traditionally engraved and ornamented], which have never borne

inscriptions.”

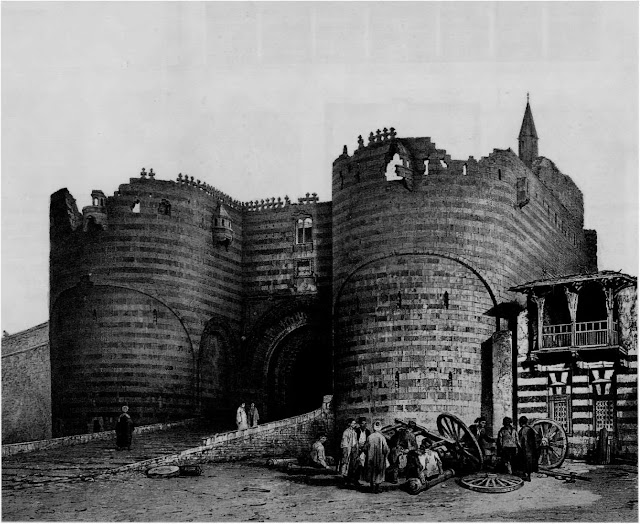

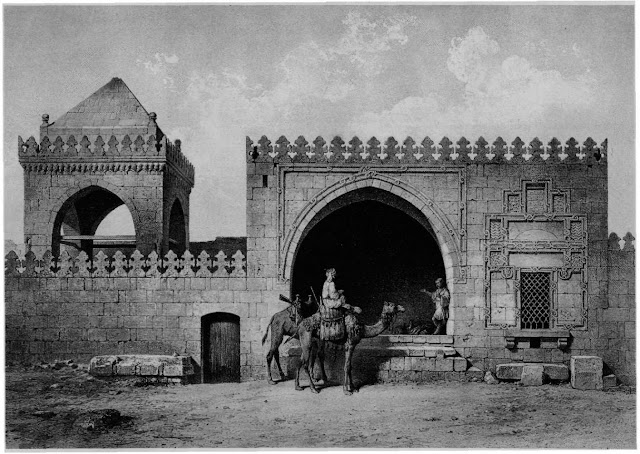

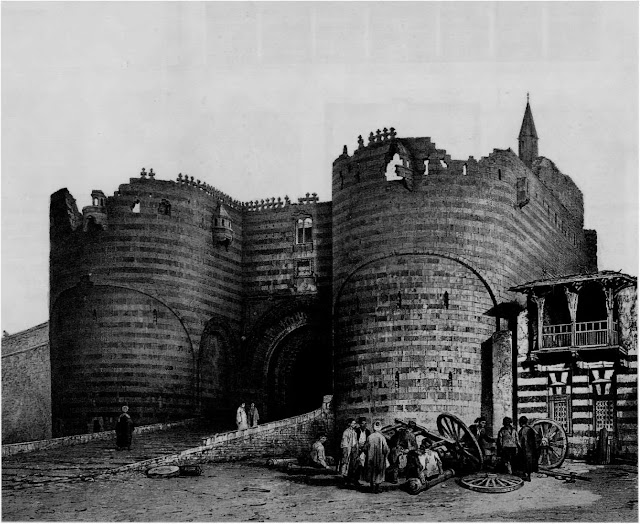

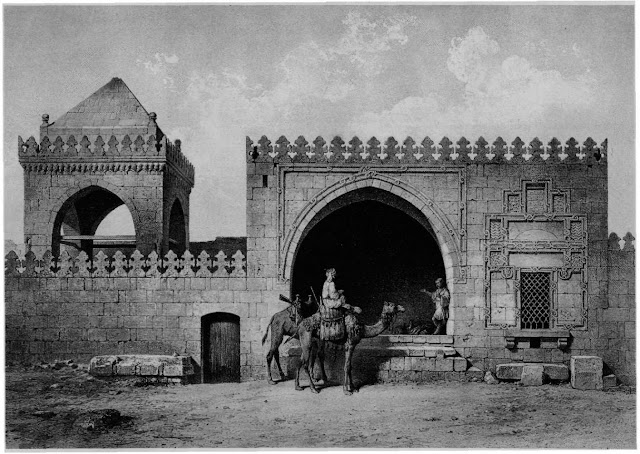

Bab al-Azab, main gate of the

Citadel, 18th century. Radwan Katkhuda’s 18th-century addition to the

Citadel provided a stage for the decisive event orchestrated under the

pretense of a feast in 1811. Muhammad Ali Pasha invited all the Mamlukes

(elite slave- soldiers) in Egypt to the fortress and had them

massacred.

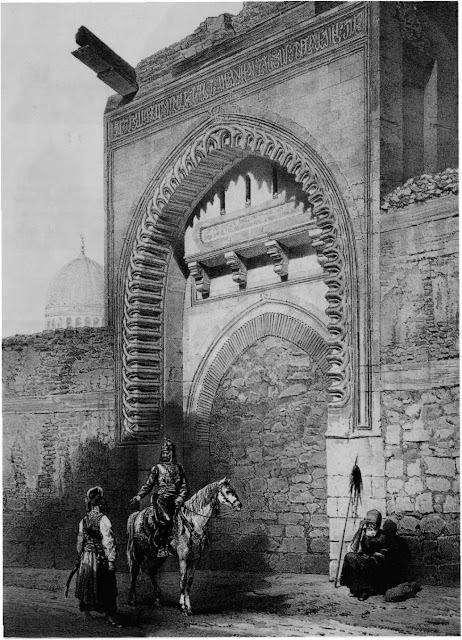

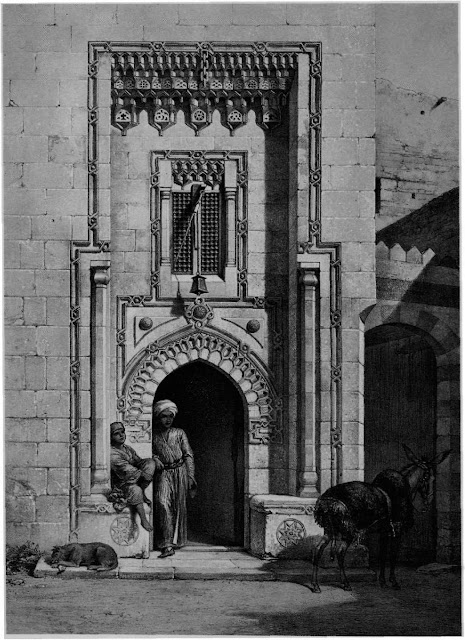

Entrance to the palace of

Sultan Baybars, 13th century. Prisse intended to convey the nature of

princely dwellings in this period when peace was fragile and the state

apparatus vulnerable to sedition. The palace’s position between the

citadel and the city provided a strategic buffer.

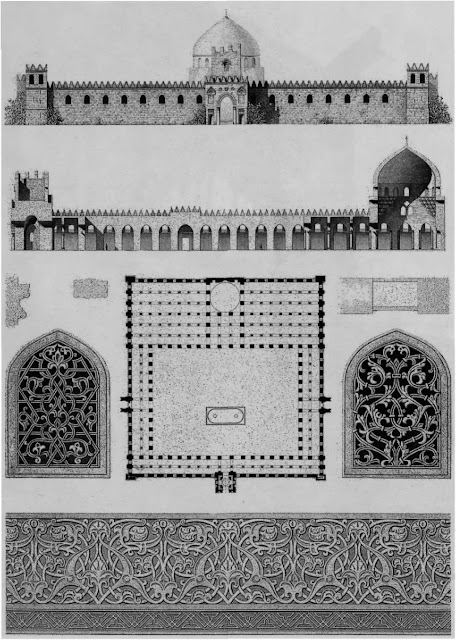

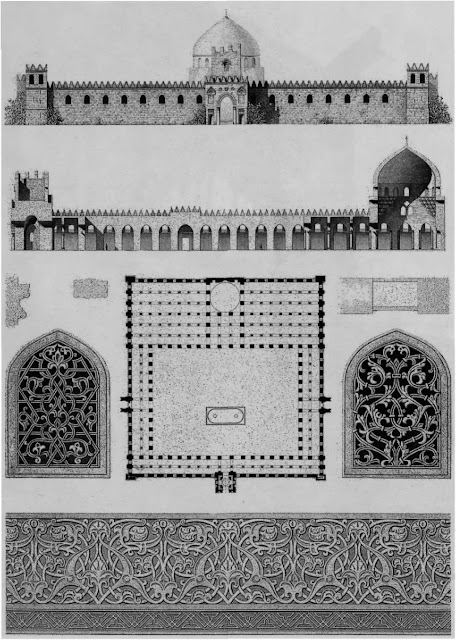

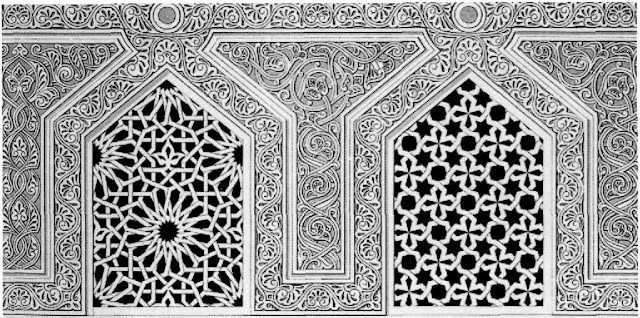

Al-Zahir mosque, plan,

elevation, & details, 13th century. Although the mosque was already

in ruins by the time of Napoleon’s expedition, Prisse, inspired by the

remnants, proposed layout schemes and parallels the fine decoration with

that of its contemporary, Granada’s Alhambra.

Tekiyat al-Shaykh Hasan

Sadaqa, 16th century. Sultan Selim added the 16th-century tekiya to a

14th-century mosque to house Mawali Sufis. The structure’s silhouette is

delineated by the dome, which nests on a cubical base, The large

circular interior was used by whirling dervishes.

Baybarsiya mosque, minaret,

14th century. The mosque, patronized by a former slave of Qalawaun, is

the oldest standing khanqa in Cairo. Its minaret once towered over

suirounding structures. The complex’s waqf document has survived and

offers insights into the daily life of 14th-century Sufis.

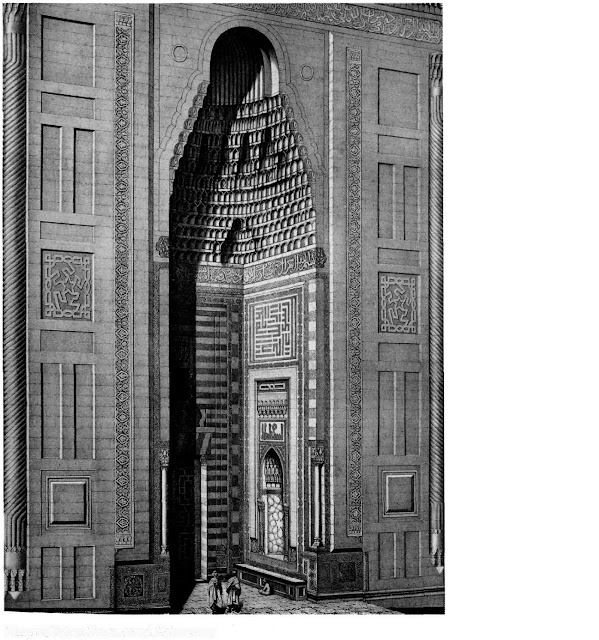

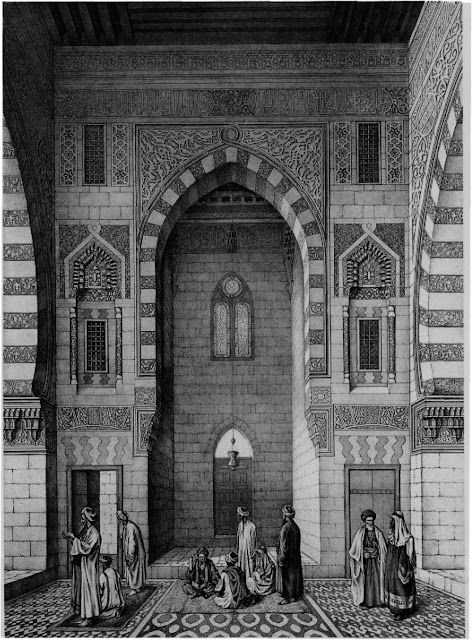

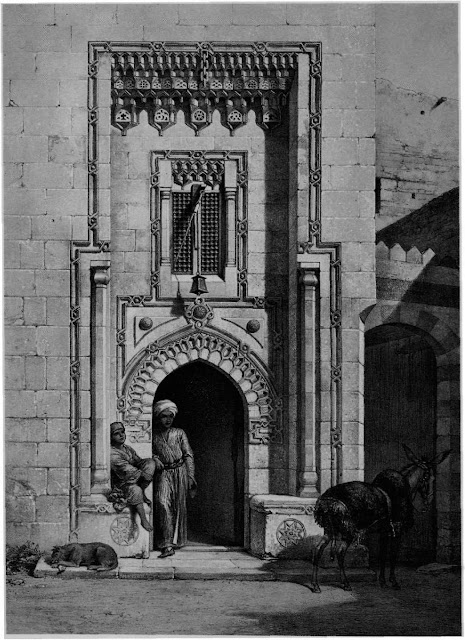

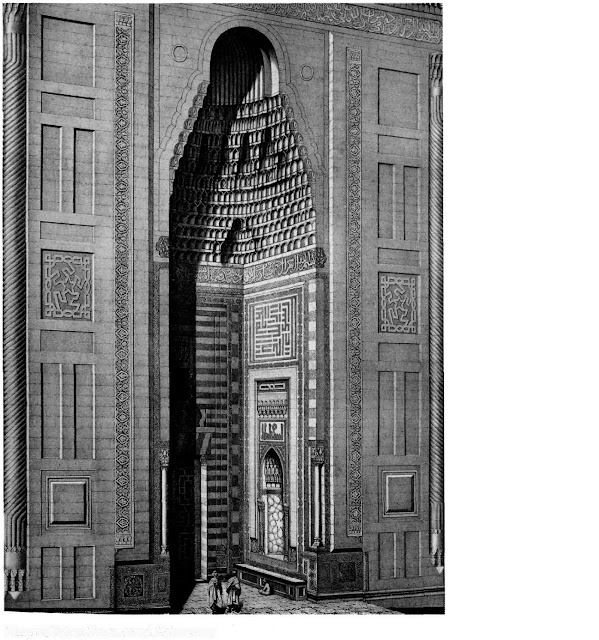

Mosque of Sultan Hasan,

porta!, 14 th century. The mosque’s portal is remarkable as an

architectural system. The artist has explored it as a functioning

independent feature and as part of the building. Columns framing inset

arches support intricate cascading muqarnas that seemingly support a

fluted half- dome.

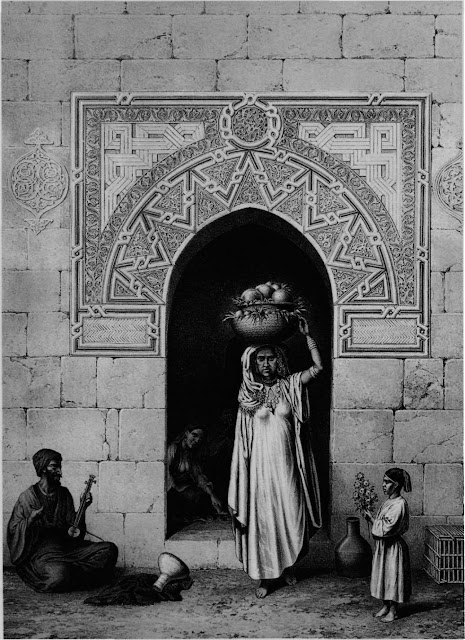

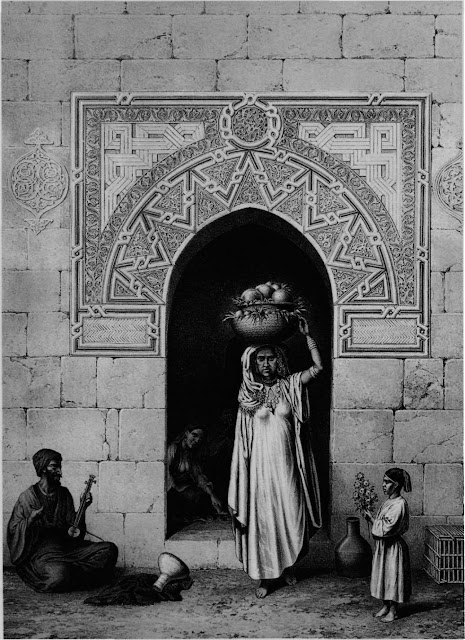

Door of a house on Sha’arawi

Street, 14th century. Popular tradition makes this door part of a qadi’s

house. Ornament was used to forge a spandrel¬like structure; this

architectonic device is traced by knots. Domestic architecture provides

insight into popular designs similar to heraldic symbols in impenal

architecture.

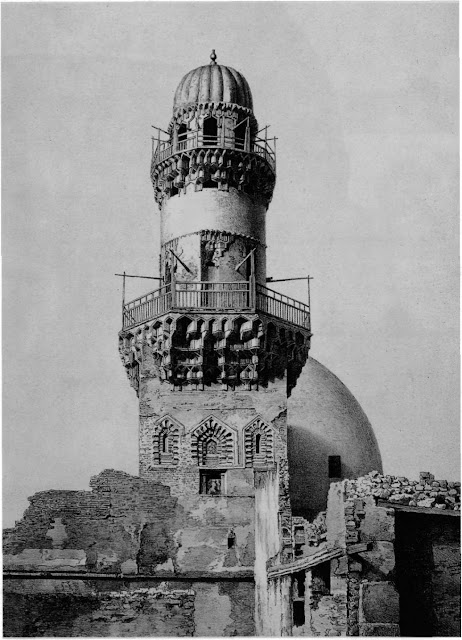

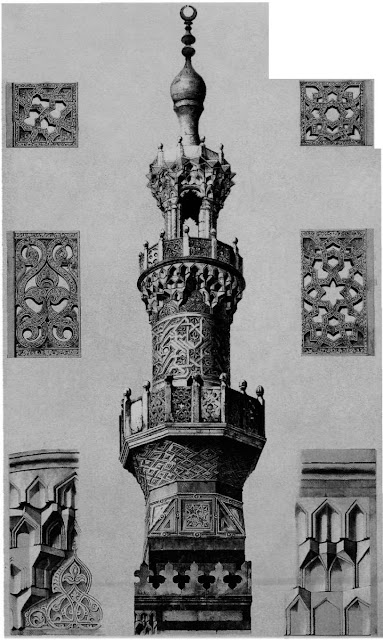

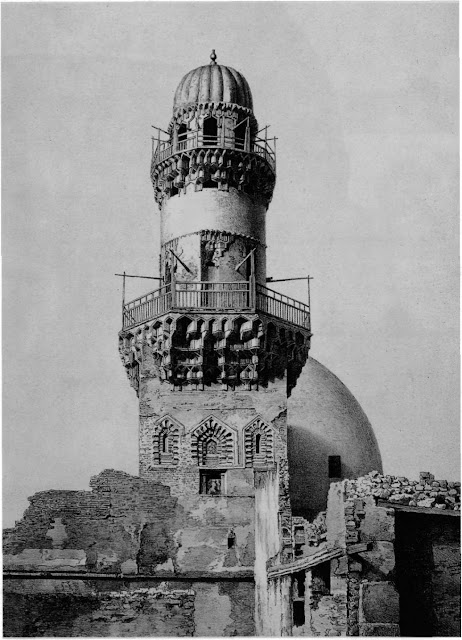

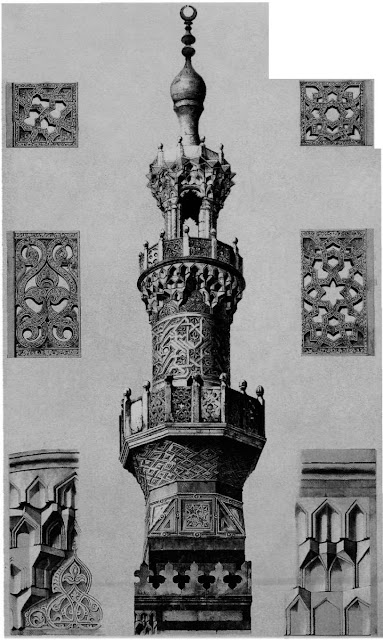

Mosque of Muhammad ihn

Qalawaun, view of the minaret, 14th century. Muqamas adorning the

mosque’s minaret elevate it into the cityscape. The minaret positions

the complex on a main avenue of medieval Cairo. Recessed panels, traced

by a knotted motif and false columns, distinguish the octagonal trunk

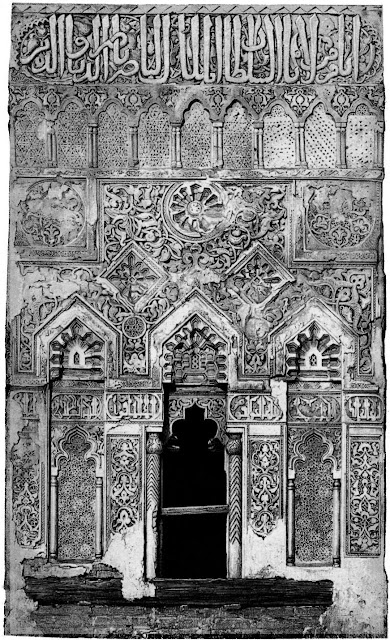

Mosque of Muhammad ibn

Qalawaun, details of the minaret, 14th century. The plate captures

intricate details of the minaret: laced, carved- stucco arabesques and

calligraphic inscriptions that draw connections with designs visible in

the interior, specifically around the mihrab.

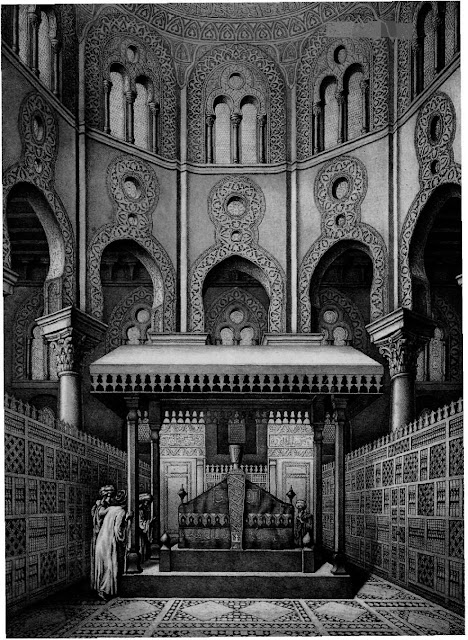

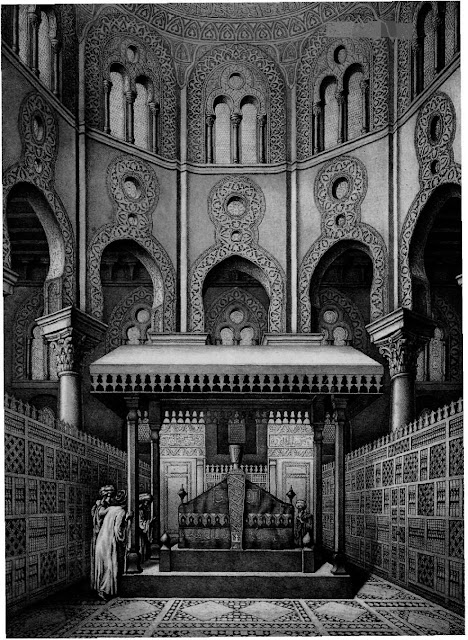

Mausoleum of Sultan Qalawaun,

14th century. The mausoleum’s symmetrical floor designs and intricate

woodwork ground the gaze, while the floor and square pillars, like a

swath of light, draw the eyes upward. The octagonal drum, composed of

two pairs of piers alternating with two pairs of columns, reflects a

debt to the Dome of the Rock,

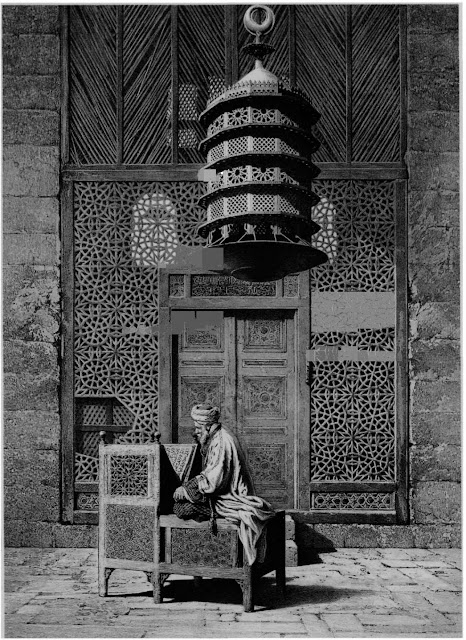

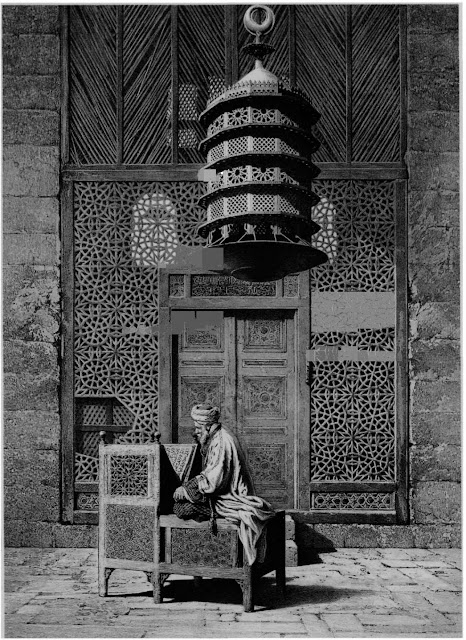

Mausoleum complex of Sultan

Barquq, door to the tomb, 14th century. The northern mausoleum, intended

for Barquq and his son Faraj, is entered through wooden lattice

screens, in front of which sits an intncately carved Quran stand. Carved

wood is set against austene

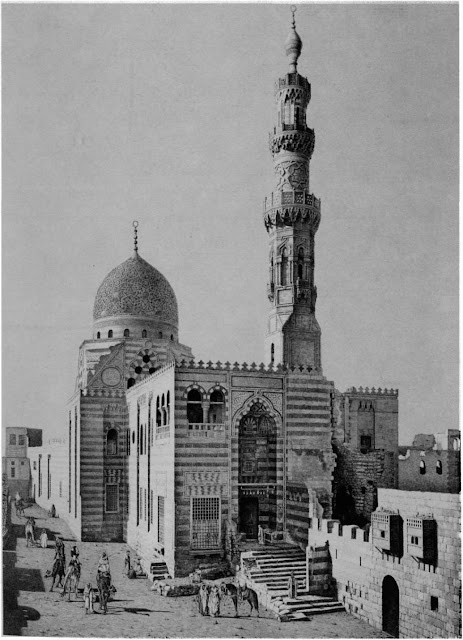

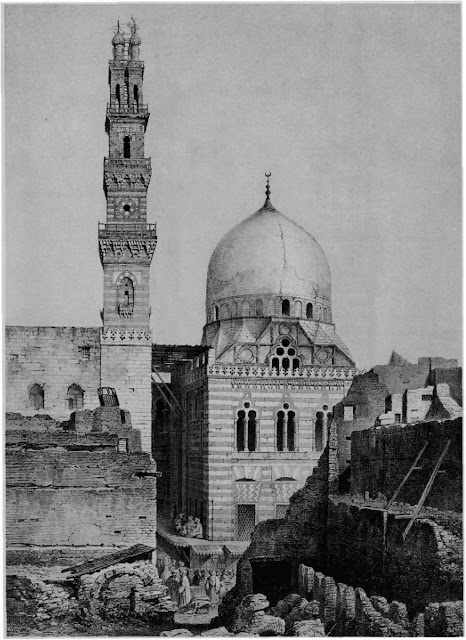

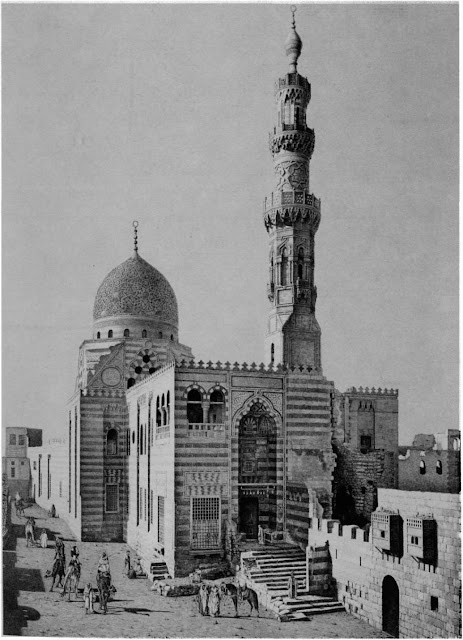

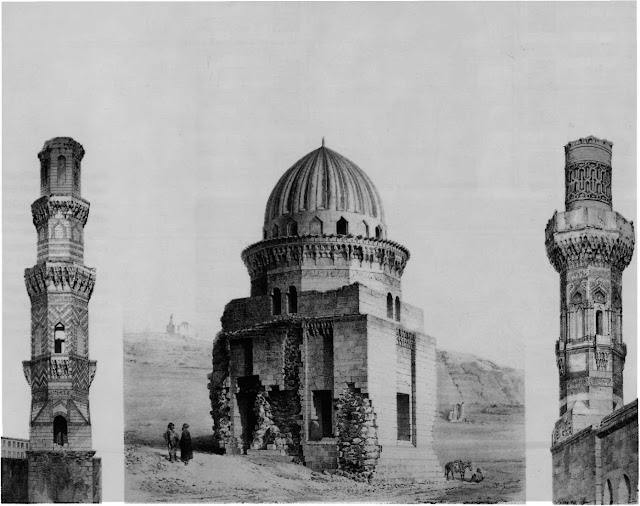

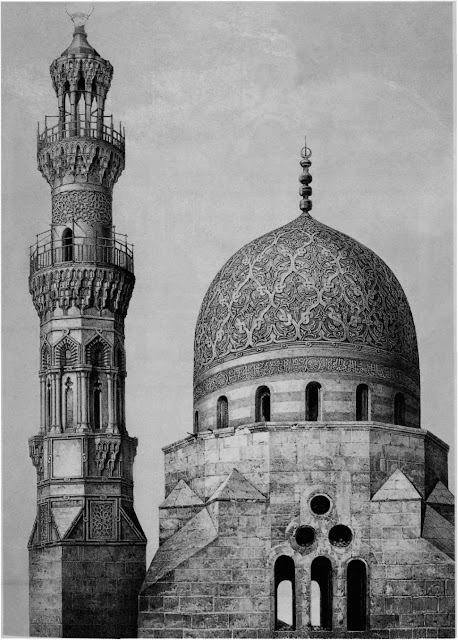

Religious-funerary complex of

Qaitbay, 15th century. At this point Cairo architectural programs were

guided by interest in fundamental Mamluke architectural forms. Balance

was conferred on an angular, seemingly asymmetrical complex by details

such as the intncate carvings on the minaret and dome.

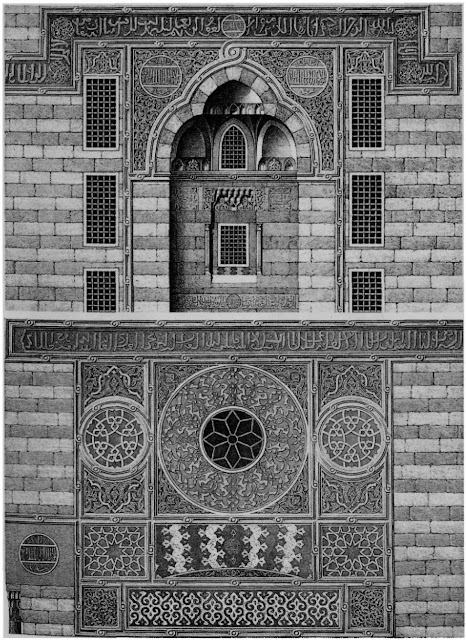

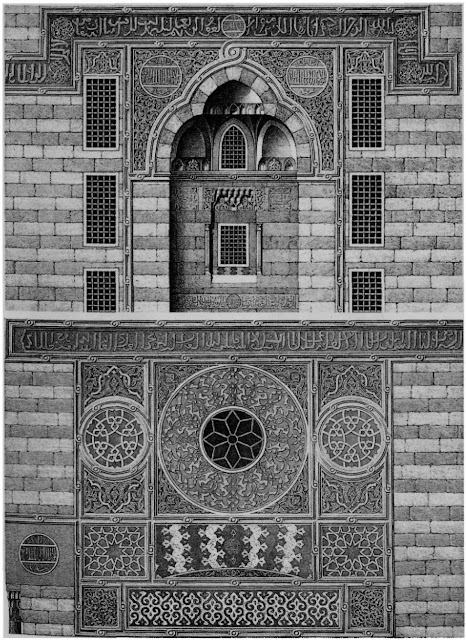

Mosque of Qaitbay, elevation

of one side, 15th century. Symmetry is not found in the mosque layout

but in the overall impact of its decoration. A lofty portal adorned with

polychrome dadoes, columned recesses, and intricate stucco carving,

frames the door that leads to the tomb. A continuous band of calligraphy

integrates the designs.

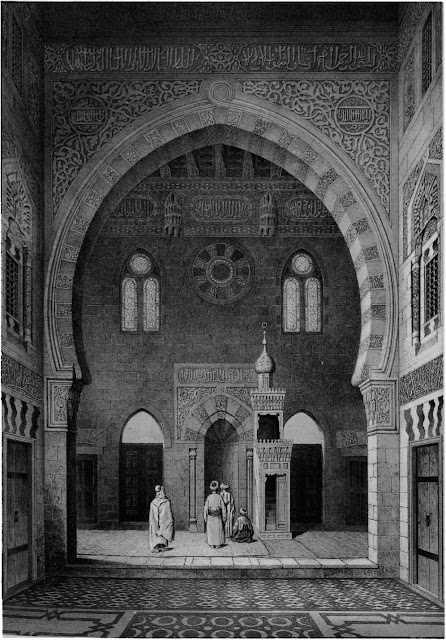

Mosque ofQaitbay, elevation

of the mihrab side, 15th century. The massive horseshoe arch framing the

mihrab suggests an unlikely airiness in this medium- sized mosque. The

qibla wall is austere, placing emphasis on its calligraphy.

Mosque of Qaitbay, ensemble

& details of the minaret, 15th century. The elegantly carved minaret

of Qaitbay’s complex displays an aesthetic more concerned with

cylindrical movements than most Mamluke minarets, which relied more

heavily on cubical base forms. Columns, used to further elevate the

structure, add lightness to its form.

Sabil Qaitbay, near Rumayleh,

part s of the facade, 15th century. This sabil on Saliba Street dates

to 1479. A trilobed arch surmounts the portal and an unusual medallion

design surmounts the iron-grated front windows that characterize sabils.

A band of calligraphy, indicated in both details, hints at the

building’s design program.

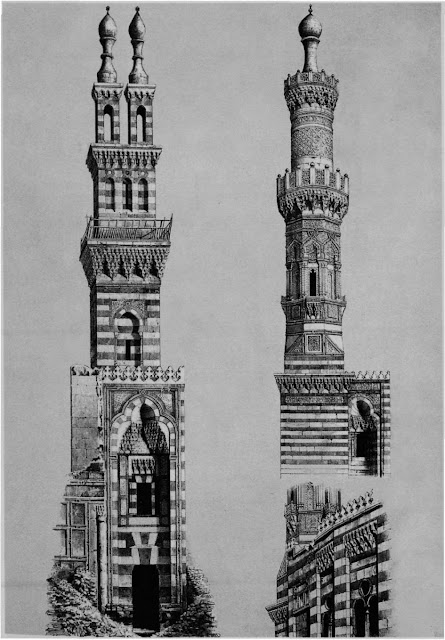

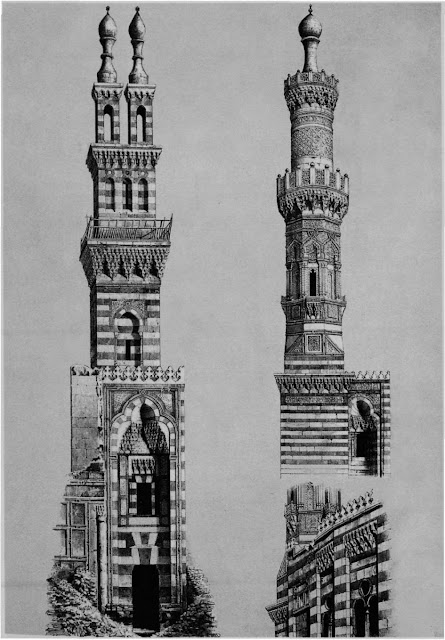

Minarets ofTurab al-lmam

mosque, 15th century, and Qalmi mosque, 16th century. This comparative

examination of the minaret of Turab al-lmam mosque and the minaret of

the Qalmi mosque reveals that both were based on an octagonal plan and

both had similar muqamas designs.

Minarets of Qanibay al-Rammah

at Nasiriya mosque, 15th century & al-Burdayni mosque, 17th

century. Contrasting minarets, cubical and cylindrical— both have

tnlobed arches, muqarnas, and alternating vertical and horizontal

voussoirs. The Nasiriya minaret exploits alternating voussoir designs

featured in the portal frame, whereas the al-Burdayni mosque displays

intricate carvings.

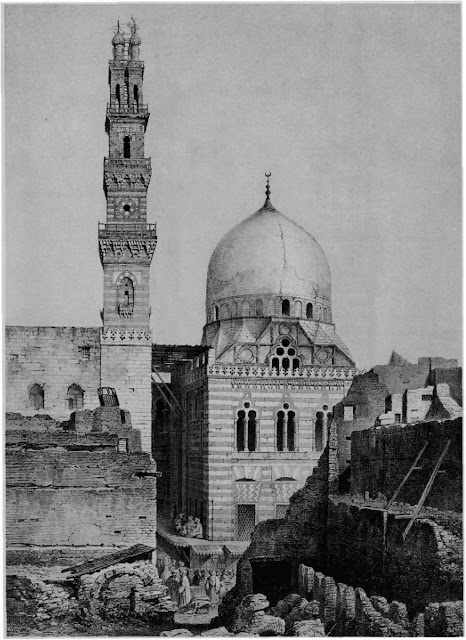

Mosque and mausoleum of

Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri, 16th century. This view highlights the

mausoleum’s dome and mosque’s minaret, which crown the mercantile area

below. The double- bulbed minaret, not part of the original structure,

was inspired by minarets from the mosques of Qanibay al-Rammah as well

as al-Ghuri at al- Azhar.

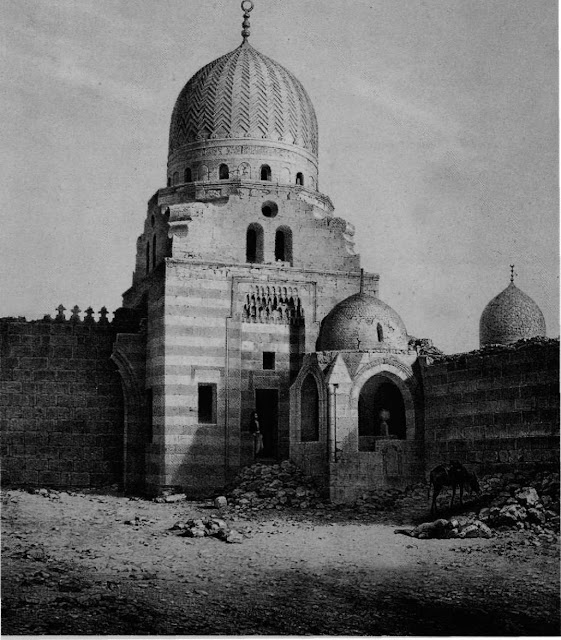

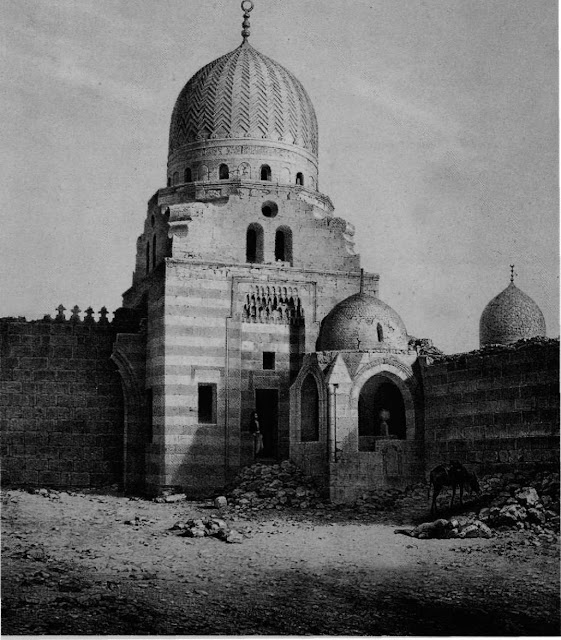

Mausoleum of Emir Tar abay

al-Sharifi, 16th century. This depiction alludes to a larger complex.

The artist has articulated the dome’s double-leaf cresting, three arched

panels surmounted by windows in the form of three oculi, and the

shoulder that decorates the transition zone.

Mausoleum of Emir Mahmud

Janum, 16th century. Prisse focused on this tomb because to his mind the

adjoining mosque bore no distinguishing features, whereas the tomb

abided wholeheartedly with prevailing Mamluke conventions. Bichrome

masonry work integrated the tomb with the whole complex.

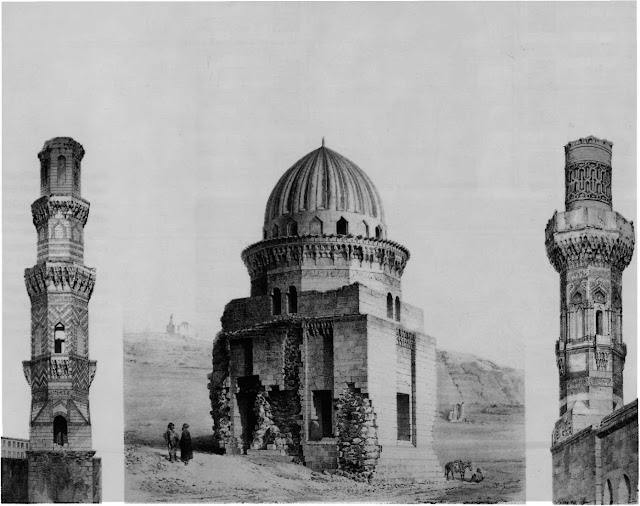

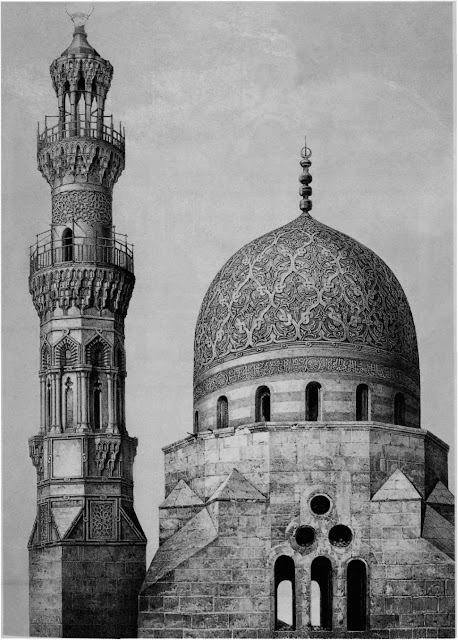

Dome and minaret of

Khayr-Bek, 16th century. Prisse discusses this essentially Mamkike

design as an anomaly. Although Emir Khayr-Bek betrayed Sultan al-Ghuri

and cooperated with the Ottomans, for which he was favored with the

governorship of Egypt, opportunism did not Override his aesthetic

sensibilities,

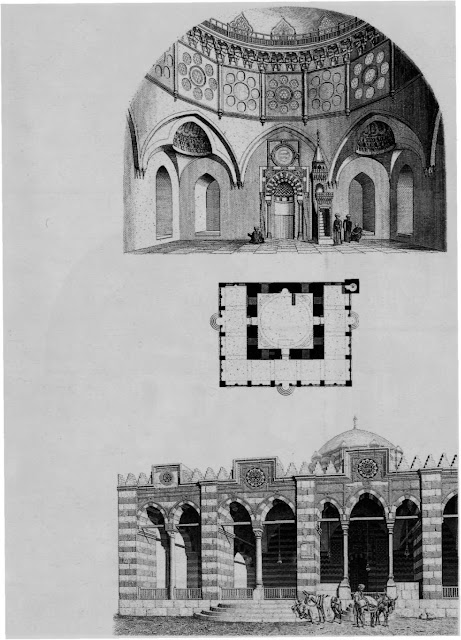

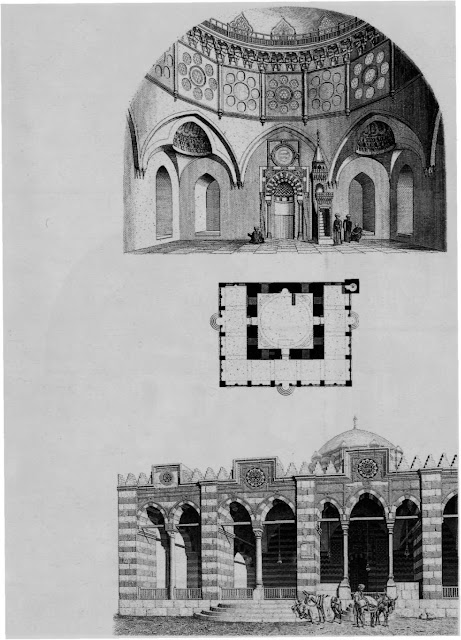

Mosque of Sinan Pasha,

elevation & plan, 16th century. Prisse’s elevations and plan of the

mosque of Sinan Pasha convey the Ottoman impact on Egyptian

architecture. He dendes self-conscious designs that boast magnificence,

highlighting the structure’s squatness and the lack of relationship

between prayer hall and sahn.

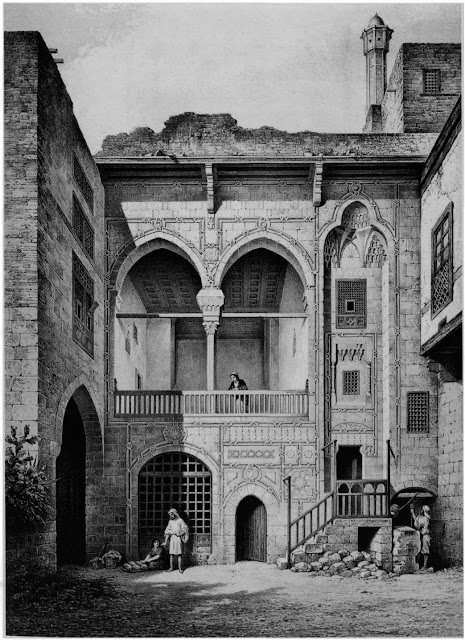

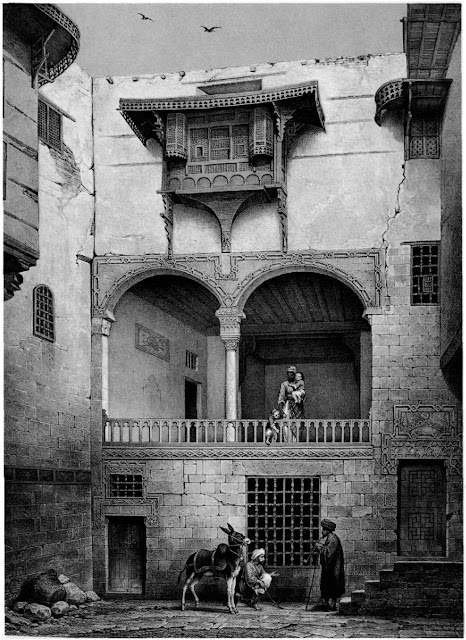

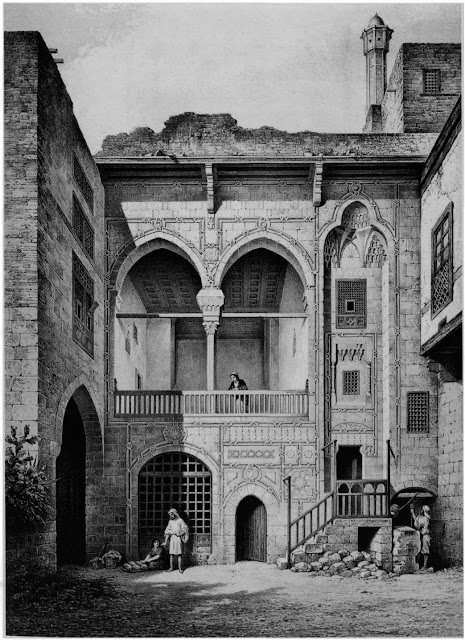

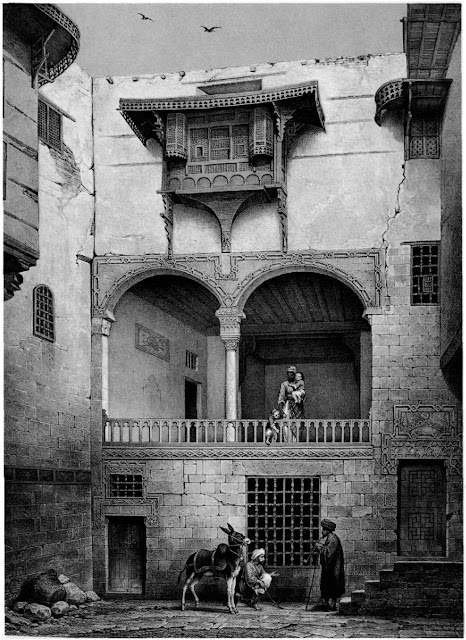

Bayt al-Emir,courtyard, 17th

century. Prisse, intngued by social history, has captured the heart of

Bayt al-Emtr— the courtyard. He examines degrees of privacy through

emphasis on several key features: the central grid window, evocative of a

sabil facade; the arch-lined hall above: and the mashrabiya coverings.

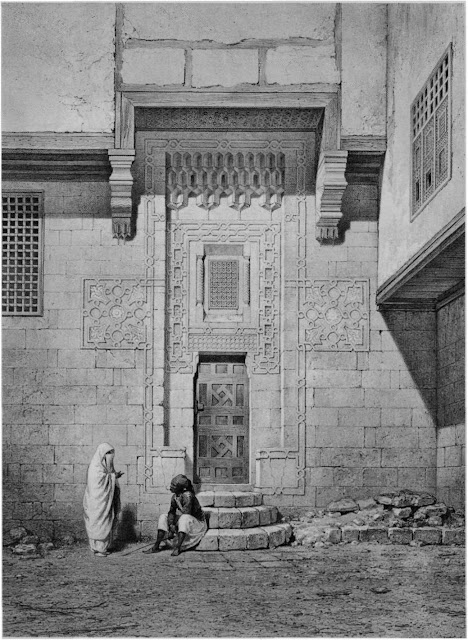

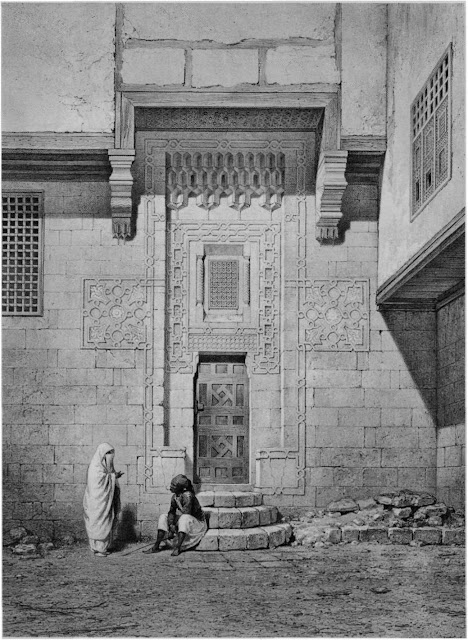

Bayt al-Emir, outer door to

the harem, 17th century. As pointed out by Prisse, harem entrances,

although elegantly adorned by carved geometnc designs and muqamas, are

quite modest so as not to invite strangers into this private space, This

depiction includes a guard, presumably a eunuch to protect the

inhabitants.

Mosque of Shaykh al-Burdayni, elevation, details, & plan, 17th century.

Funerary mosque near Kiman

al-Jiyushi, 18th century. This mosque shows how various edifices were

grouped around tombs. The facade shows a small room where travelers and

passers-by could stay or rest Next to the tomb, crowned by a pyramidal

dome, is a sabil-kuttab—a school and cistern.

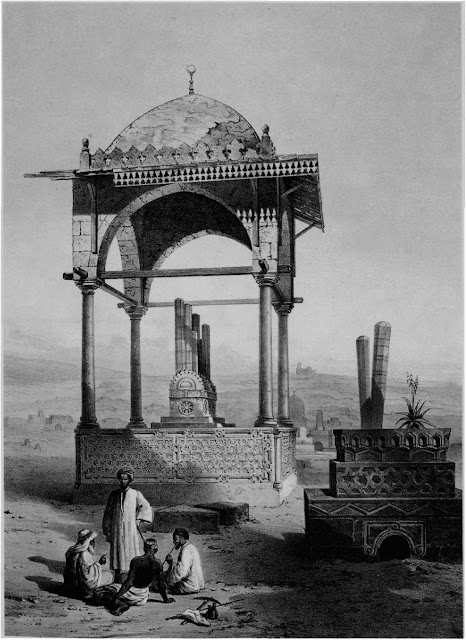

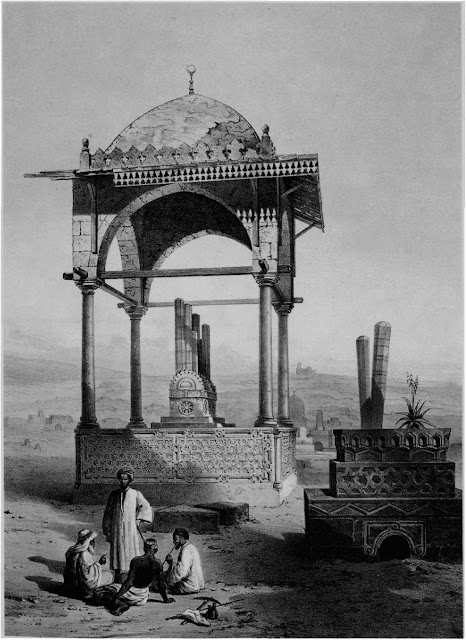

Tombojan emir in the Qarafa

cemetery, 18th century. This tomb in the southern cemetery (Qarafa) is

defined by its elegant columns and light dome which effects airiness and

modesty. The canopied dome is typical of tombs that from the Mamluke

period onward could be purchased ready-designed.

Sabil Ahmad Husayn Marjush,

18th century. Typical of its genre and time, this sabil adheres to

Prisse’s formulaic model for sabil layout. The sabil, an institution

integral to the community as a source of water, juts into the street,

revealing its presence to the passerby.

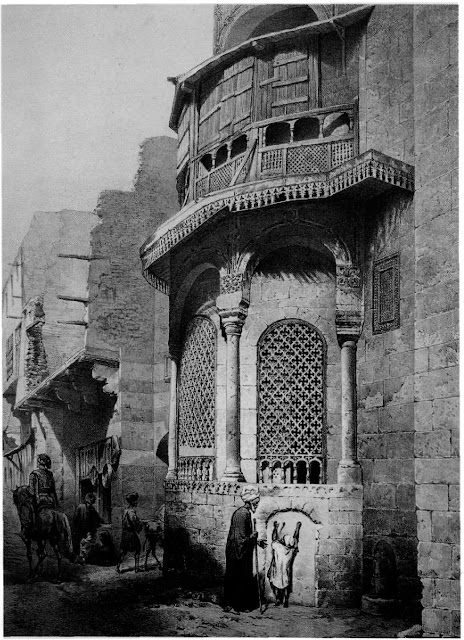

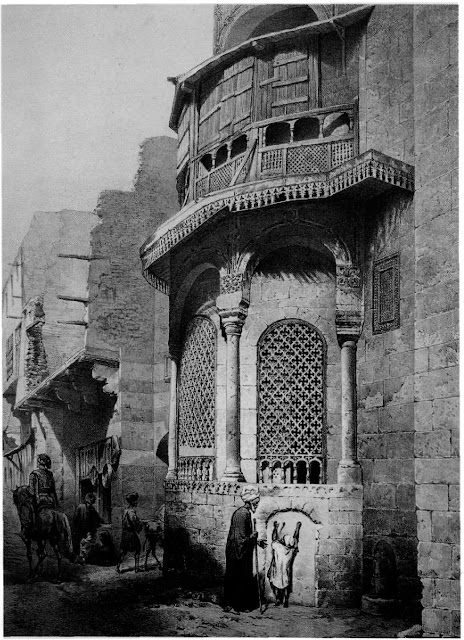

Zamyat Abd al-Rahman

Katfchuda, 18th century. In 1729. Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda built a zawiya—

housing for Sufis—on two levels above a few shops. This was but one of

his contributions to Cairo’s cityscape. Prisse draws parallels between

its decoration and that of European Renaissance styles.

Door of the bath Hammam

al-Talat, 18th century. This delightful rendition of the door to Hammam

al- Talat located in the medieval Jewish quarter reveals an original

approach to design. A stone chain, chiseled out of limestone, seems to

have included a hook-like fixture for a hanging lamp.

Bayt al-Shalabi, courtyard,

18th century. With Prisse’s focus on details at multiple depths. The

complexities of domesticity emerge. Private and public space are

explored wrth social constructs that position people in the building:

male servants busy themselves on the ground, a female servant looks on

from above, while cloistered ladies are presumably hidden behind the

mashrabiya.

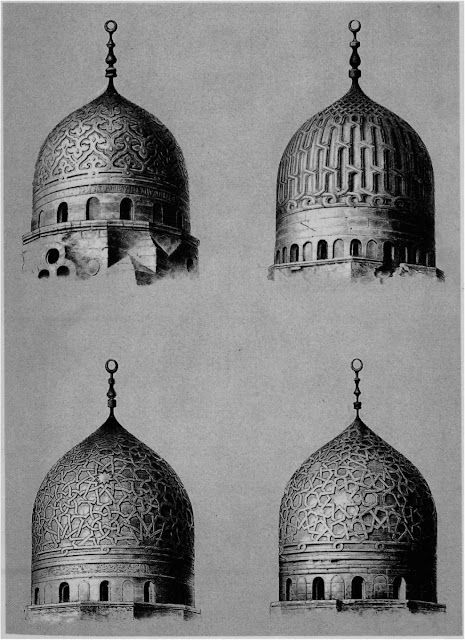

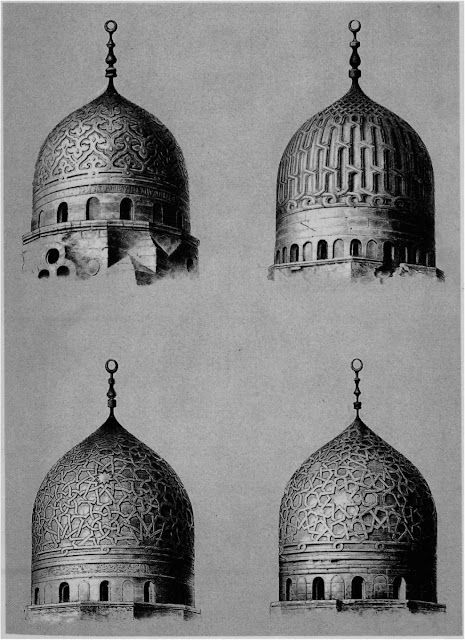

Domes: Although Prisse

attributes stylistic significance to domes, he treats them randomly and

not as reflective of transfers and adaptations of building technology.

These four designs, though essentially linear, embody dense, fleshy

arabesques typical of later Mamluke domes.

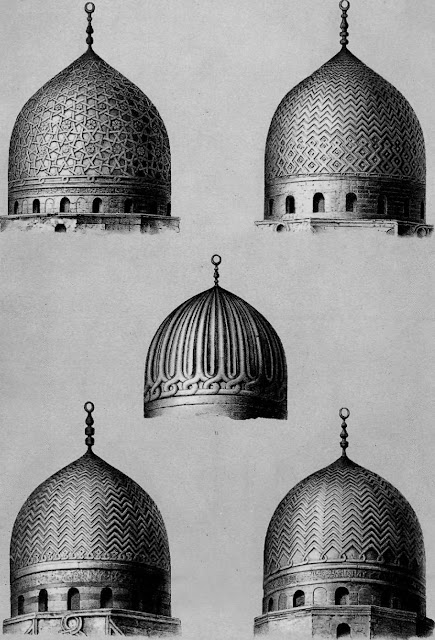

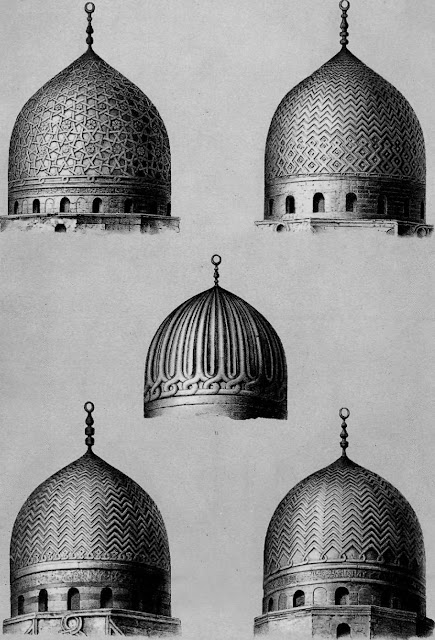

Stone as opposed to brick is

the underlying theme in this set of domes. The central dome displays an

interpretation of functional brick ribs into architectonic stone ones.

Further developments, particularly zigzagged designs, lighten solid

stone ribs with changes of direction at vertical joints, (9) Sultan

Barsbay, Khanqa mausoleum (1432): (10) Emir Qunqmas (1506); (I I)

Emirlnal al-Yusufi (1392-93); (12) Emir Ganibak at the madrasa

(1426-27); and (13) Khanqa of Faraj ibn Barquq (141 I).

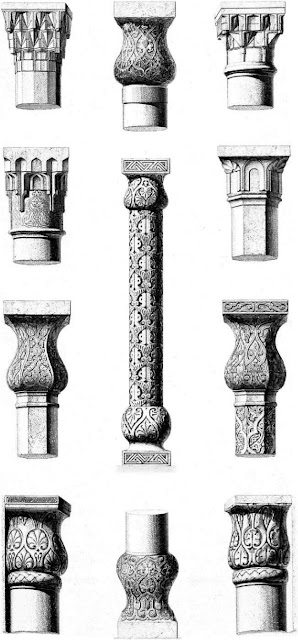

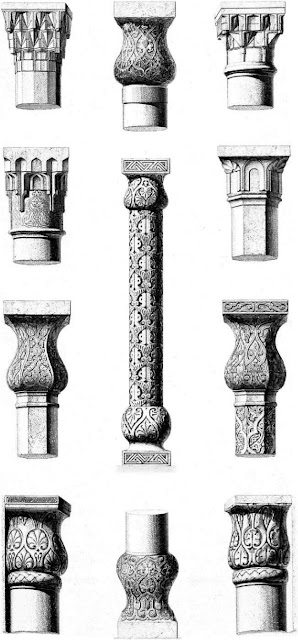

Columns & pillars,

ensemble & details. Columns and pillars serve a universal function

but bear vaned ornamentation. Often removed from one building to be used

in another, they could be a key medium for transmitting designs, an

attractive idea when materials like marble were not available locally.

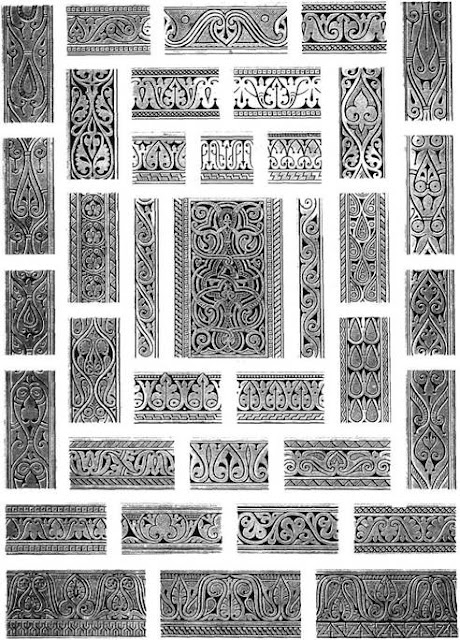

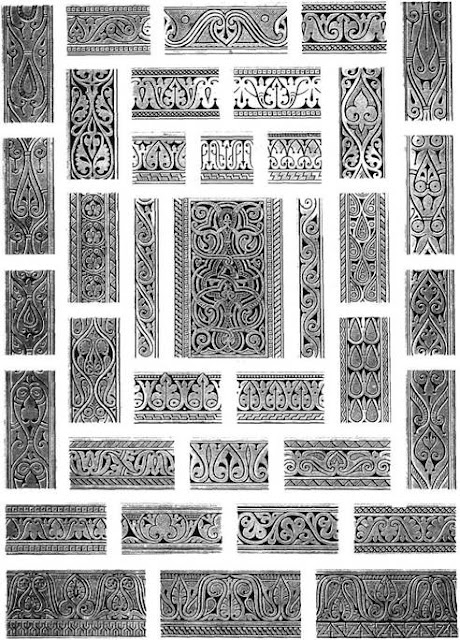

Mosque of Ahmad ibn Tulun,

ornamental details, 9th century. Three distinct patterns taken from

Samarra are combined and mixed, providing schemes of ornament that frame

arches and decorate soffits. Central are pointed leaves, some of which

blossom into a trefoil, and short thick undulated stems which converge

at the top.

Fragments of the dome’s exterior ornamentation

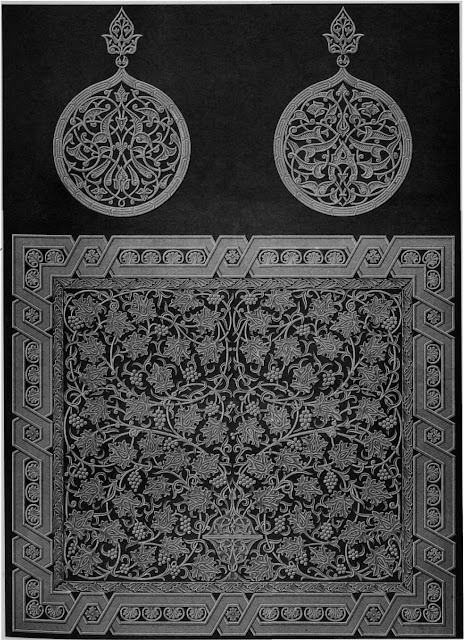

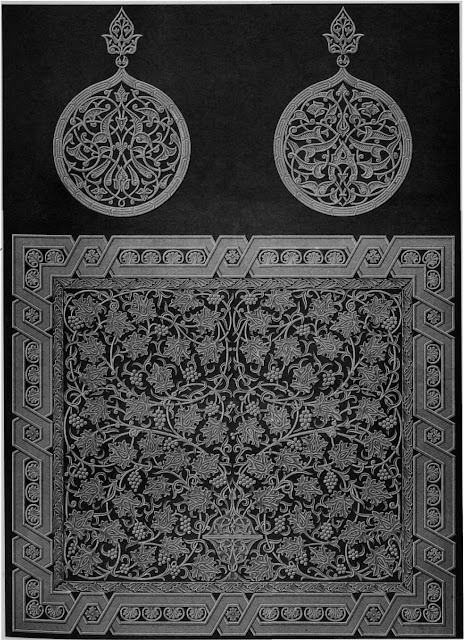

Bayt al-Emir, crowning of the

bath door, 17th century. Despite its decay, in Prisse’s time this

exhibited remnants of two different illuminated designs. The vine leaves

emerging from the vase appear to have been gilded. Elsewhere the leaves

were pale green, vine branches dark green, and grapes blue.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق