The Tomb of Meketre

(translates to The Sun is my protection) in western Thebe was a high official during the reign of Mentuhotep II, Mentuhotep III, Mentuhotep IV and Amenemhat I which spanned the 11th and 12th Dynasties. He served as Overseer of the Six Great Law Courts, Treasurer and Chief Steward. He died during the early years of Amenemhat’s reign and was one of the last high-officials to be buried at Thebes before the royal court moved to Lisht. All the accessible rooms in the tomb of Meketre had been robbed and plundered during Antiquity; but early in 1920 the Museum’s excavator, Herbert Winlock, wanted to obtain an accurate floor plan of the tomb’s layout for his map of the Eleventh Dynasty necropolis at Thebes and, therefore, had his workmen clean out the accumulated debris. It was during this cleaning operation that the small hidden chamber was discovered, filled with twenty-four almost perfectly preserved models. Eventually, half of these went to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and the other half came to the Metropolitan Museum in the partition of finds.

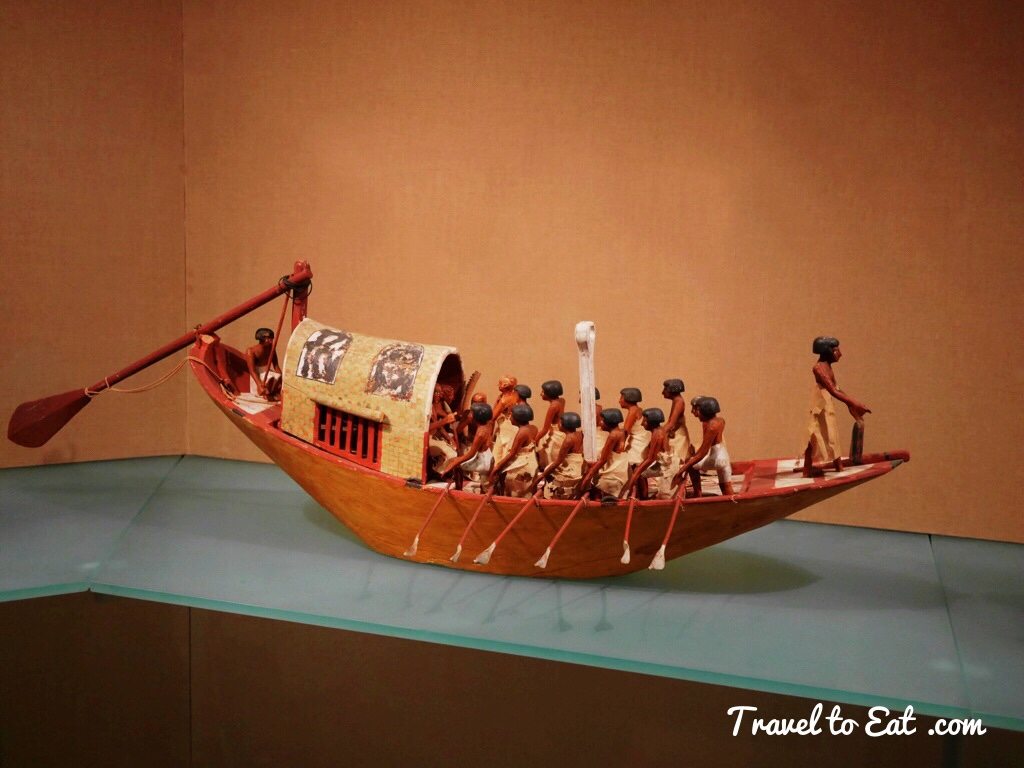

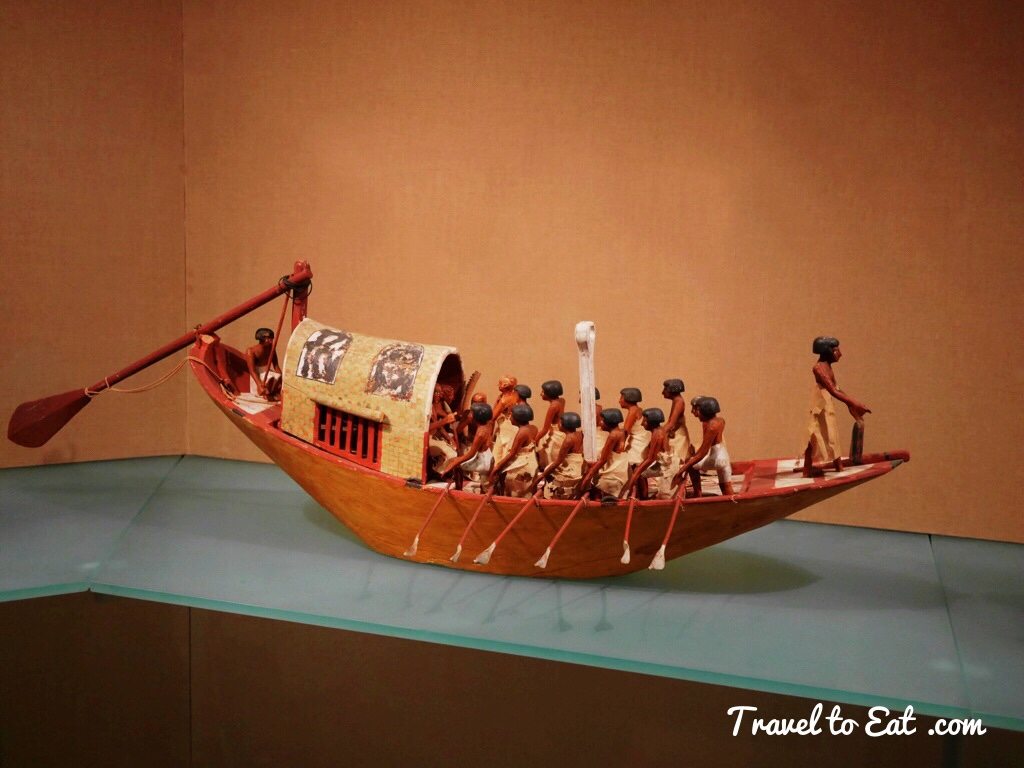

This boat is being paddled northward—downstream but against the

prevailing wind—by sixteen men whose varied size and arm positions

create an impression of movement along the line. The boat has two

rudders because the elaborate stern would not accommodate the single

rudder that was common to ordinary boats of the time. The rudders are

fixed to poles capped by falcon heads. A statue-like figure of Meketre

sits under a baldachin (canopy). The presence of a large libation vase

indicates that an offering ritual is being performed. Facing Meketreis

one of his sons or an upper servant with arms crossed reverentially over

his chest. The shape of the boat, the baldachin, and the vase testify

to the funerary nature of the voyage. Quite possibly, we are seeing

Meketre on a pilgrimage to Abydos, the sacred site of Osiris, the god of

the underworld. Note that all figures on this boat have shaven heads.

This boat is being paddled northward—downstream but against the

prevailing wind—by sixteen men whose varied size and arm positions

create an impression of movement along the line. The boat has two

rudders because the elaborate stern would not accommodate the single

rudder that was common to ordinary boats of the time. The rudders are

fixed to poles capped by falcon heads. A statue-like figure of Meketre

sits under a baldachin (canopy). The presence of a large libation vase

indicates that an offering ritual is being performed. Facing Meketreis

one of his sons or an upper servant with arms crossed reverentially over

his chest. The shape of the boat, the baldachin, and the vase testify

to the funerary nature of the voyage. Quite possibly, we are seeing

Meketre on a pilgrimage to Abydos, the sacred site of Osiris, the god of

the underworld. Note that all figures on this boat have shaven heads.

Meketre is seated smelling a lotus blossom in the shade of a small

cabin, which on an actual boat would have been made of a light wooden

framework with linen or leather hangings. Here the hangings are shown

partly rolled up to let the breeze into the cabin. Wooden shields

covered with bulls’ hides are painted on each side of the cabin roof. A

singer, with his hand to his lips, and a blind harper entertain Meketre

on his voyage. Standing in front of him is a man, probably the ship’s

captain, with his arms crossed over his chest. He may be depicted

awaiting orders, but he may also be paying homage to the deceased

Meketre. As the twelve oarsmen propel the boat, a lookout in the bow

holds a weighted line used to determine the depth of the river. At the

stern, the helmsman controls the rudder. A tall white post amidship

supported a mast and sail (not found in the tomb), which would have been

taken down when the boat was rowed downstream—as it is here—against the

prevailing north wind. Going south (upstream), with the wind behind it,

the boat would have been sailed.

Meketre is seated smelling a lotus blossom in the shade of a small

cabin, which on an actual boat would have been made of a light wooden

framework with linen or leather hangings. Here the hangings are shown

partly rolled up to let the breeze into the cabin. Wooden shields

covered with bulls’ hides are painted on each side of the cabin roof. A

singer, with his hand to his lips, and a blind harper entertain Meketre

on his voyage. Standing in front of him is a man, probably the ship’s

captain, with his arms crossed over his chest. He may be depicted

awaiting orders, but he may also be paying homage to the deceased

Meketre. As the twelve oarsmen propel the boat, a lookout in the bow

holds a weighted line used to determine the depth of the river. At the

stern, the helmsman controls the rudder. A tall white post amidship

supported a mast and sail (not found in the tomb), which would have been

taken down when the boat was rowed downstream—as it is here—against the

prevailing north wind. Going south (upstream), with the wind behind it,

the boat would have been sailed.

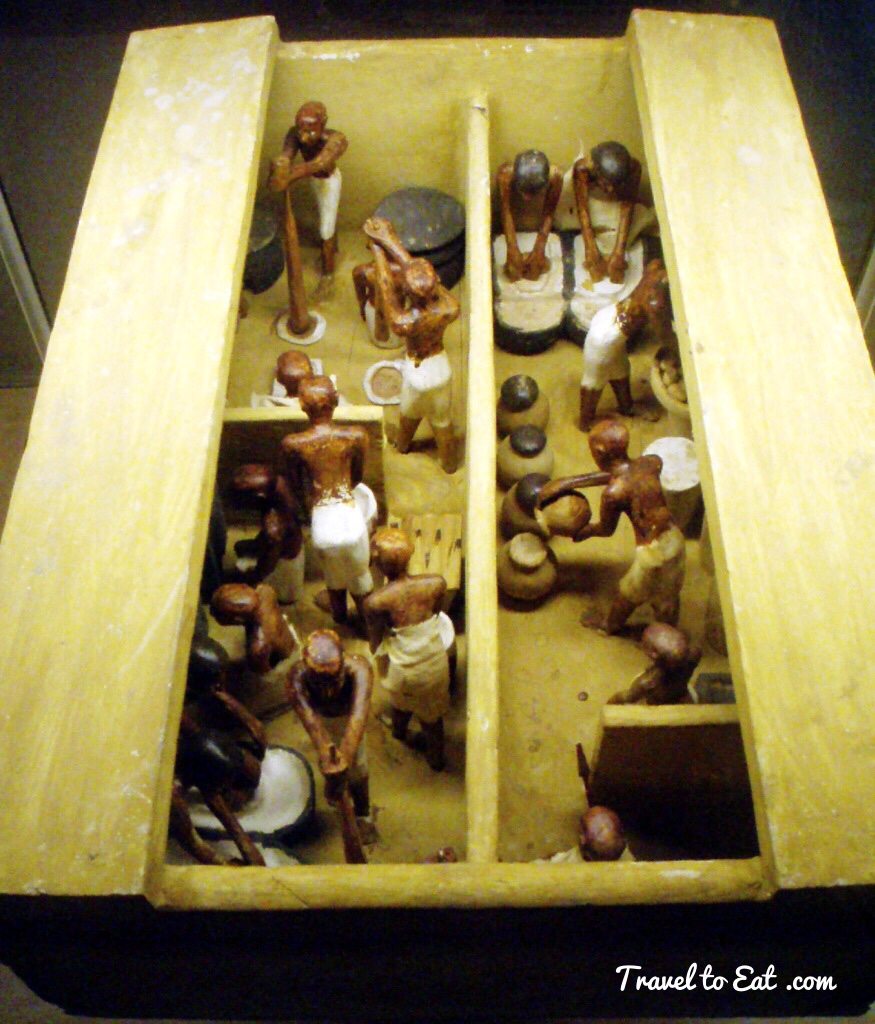

Many outings of Egyptian nobles culminated in a picnic. On the menu

for Meketre’s boat trip were roasted fowl,dried beef, bread, beer, and

some kind of soup. Meat and bread were carried on another tender, now in

Cairo. Here, the beer is prepared and the soup cooked. A blackened

trough may have contained burning coal forroasting the fowl. A man tends

a stove on which soup simmers. On either side, a woman grinds grain.

Brewers inside the cabin are shaping bread loaves, then working them

through sieves into large vats. One brewer stands in another vat, where

he tramples the dates that provide the sugar for the fermentation of the

beer. The oars of this boat are fixed to the sides; to avoid damaging

the oars while the boats were transported and deposited in the model

chamber, all oars of Meketre’s boats were secured in this manner.

Many outings of Egyptian nobles culminated in a picnic. On the menu

for Meketre’s boat trip were roasted fowl,dried beef, bread, beer, and

some kind of soup. Meat and bread were carried on another tender, now in

Cairo. Here, the beer is prepared and the soup cooked. A blackened

trough may have contained burning coal forroasting the fowl. A man tends

a stove on which soup simmers. On either side, a woman grinds grain.

Brewers inside the cabin are shaping bread loaves, then working them

through sieves into large vats. One brewer stands in another vat, where

he tramples the dates that provide the sugar for the fermentation of the

beer. The oars of this boat are fixed to the sides; to avoid damaging

the oars while the boats were transported and deposited in the model

chamber, all oars of Meketre’s boats were secured in this manner.

This boat is being rowed in a northerly direction, downstream,

against the prevailing north wind. Its mast and spars rest in the

forklike support beam, ready to be rigged for the return journey. The

sail lies folded on the deck. A small cabin, positioned amidships,

leaves room for eighteen rowers; speed clearly is important on this

journey. Seated on a stool in the prow, Meketre holds a closed lotus

flower to his nose. Before him stands a man (possibly the boat captain),

with arms crossed referentially over his chest. Inside the cabin, a

servant guards Meketre’s trunk. Is the Chief Steward on an inspection

tour for the pharaoh, and does the trunk contain the accounts? Even if

this represents a real-life event, the model still refers to the

afterlife because the lotus flower, which opens every morning when the

sun comes up, is a symbol of rebirth.

This boat is being rowed in a northerly direction, downstream,

against the prevailing north wind. Its mast and spars rest in the

forklike support beam, ready to be rigged for the return journey. The

sail lies folded on the deck. A small cabin, positioned amidships,

leaves room for eighteen rowers; speed clearly is important on this

journey. Seated on a stool in the prow, Meketre holds a closed lotus

flower to his nose. Before him stands a man (possibly the boat captain),

with arms crossed referentially over his chest. Inside the cabin, a

servant guards Meketre’s trunk. Is the Chief Steward on an inspection

tour for the pharaoh, and does the trunk contain the accounts? Even if

this represents a real-life event, the model still refers to the

afterlife because the lotus flower, which opens every morning when the

sun comes up, is a symbol of rebirth.

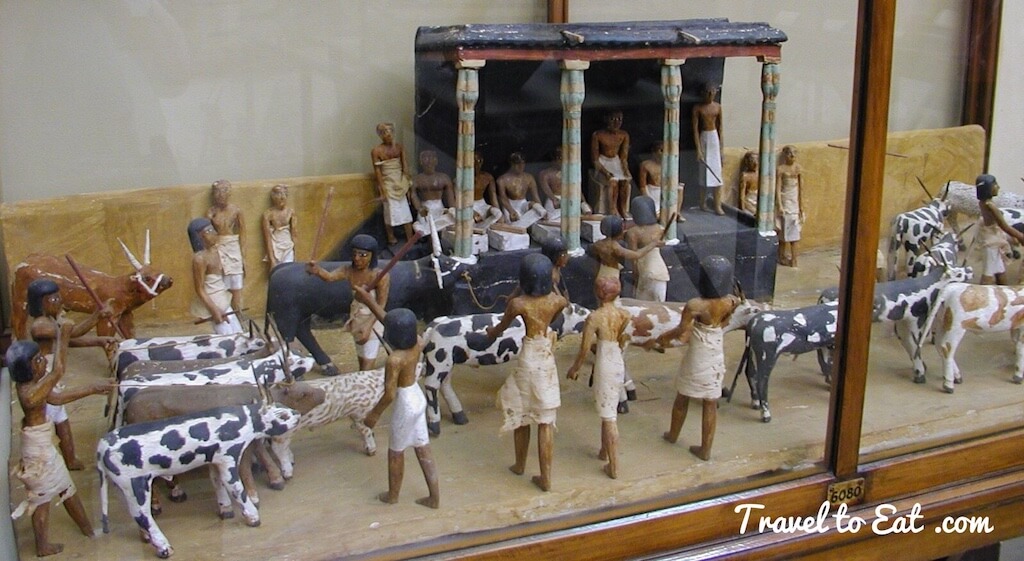

These models are highly valued because of the exquisite carving and

painting and because they are remarkably well preserved. The colours,

the linen garments on some of the figures, and most of the twine rigging

on the boats are original. They tell us in great detail about the

raising and slaughtering of livestock, storage of grain, making of bread

and beer, and design of boats in Middle Kingdom Egypt. On another level

of meaning, they tell us about the Egyptian belief that images could

magically provide safe passage to the afterlife and eternal sustenance

once there. Because of limited space, only the models above were on

display when I visited. I found another collection on Wikipedia that

shows dioramas of A garden, making bread and beer and a livestock

market.

These models are highly valued because of the exquisite carving and

painting and because they are remarkably well preserved. The colours,

the linen garments on some of the figures, and most of the twine rigging

on the boats are original. They tell us in great detail about the

raising and slaughtering of livestock, storage of grain, making of bread

and beer, and design of boats in Middle Kingdom Egypt. On another level

of meaning, they tell us about the Egyptian belief that images could

magically provide safe passage to the afterlife and eternal sustenance

once there. Because of limited space, only the models above were on

display when I visited. I found another collection on Wikipedia that

shows dioramas of A garden, making bread and beer and a livestock

market.

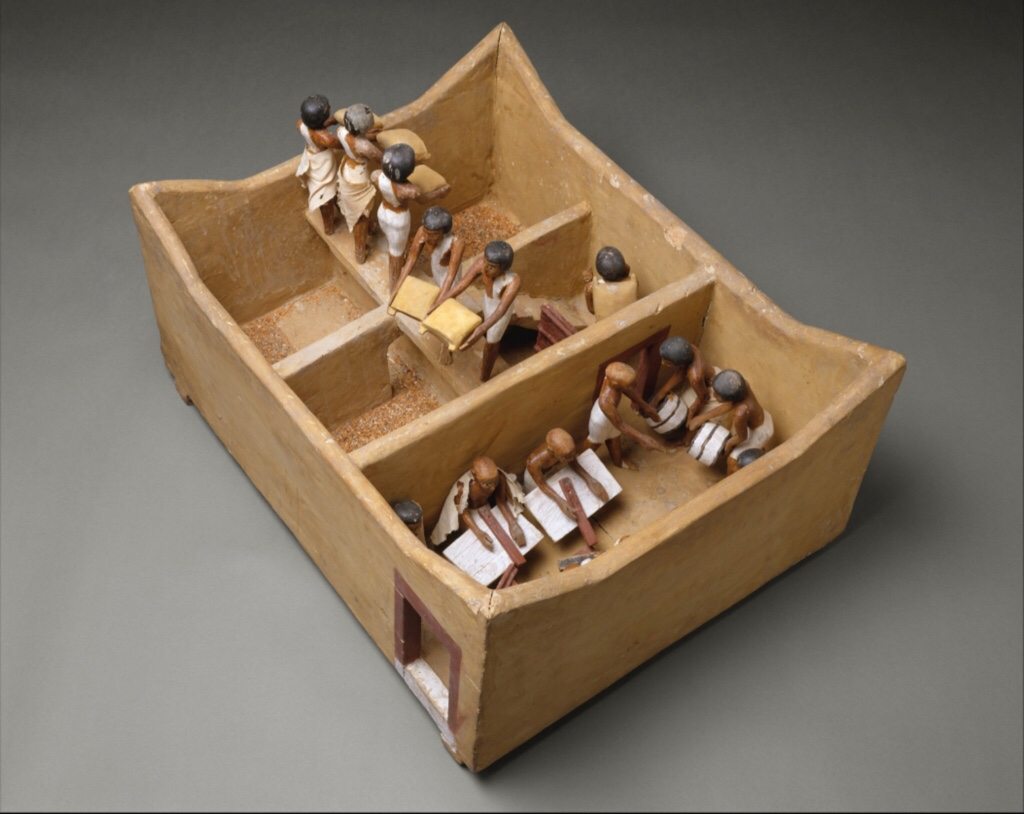

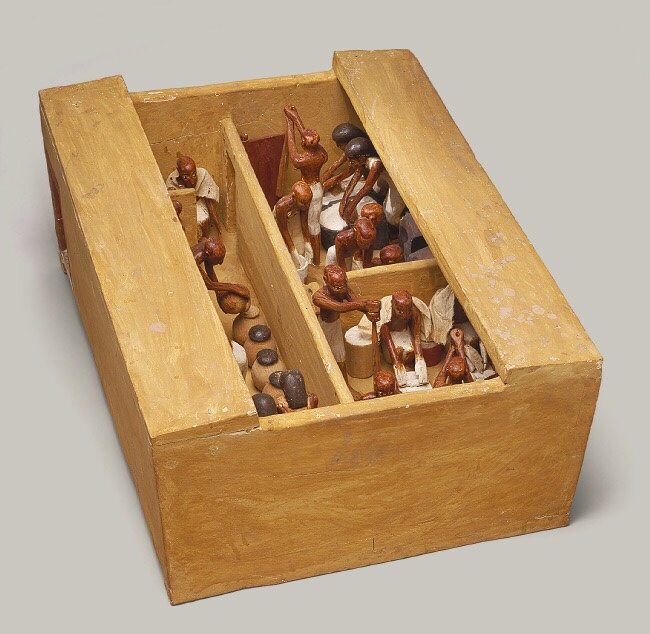

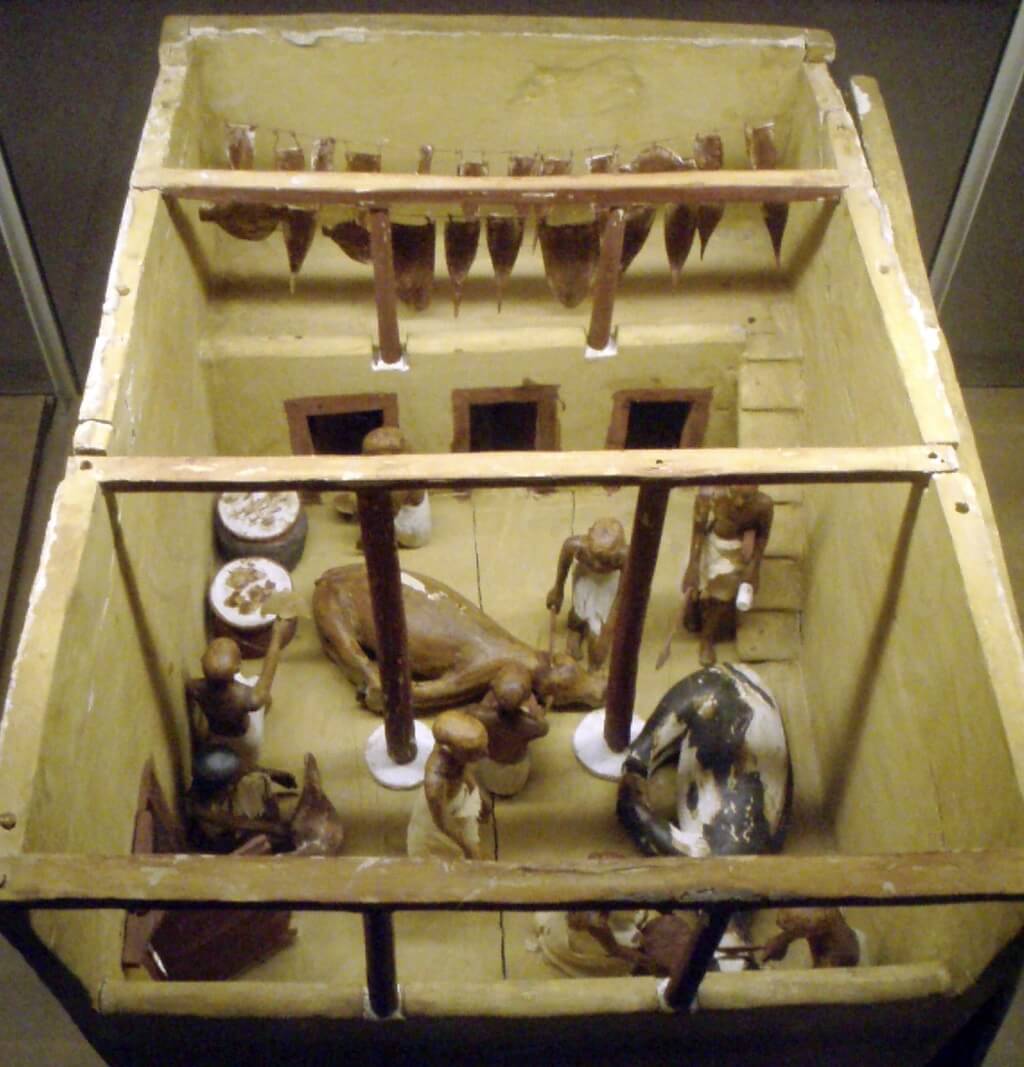

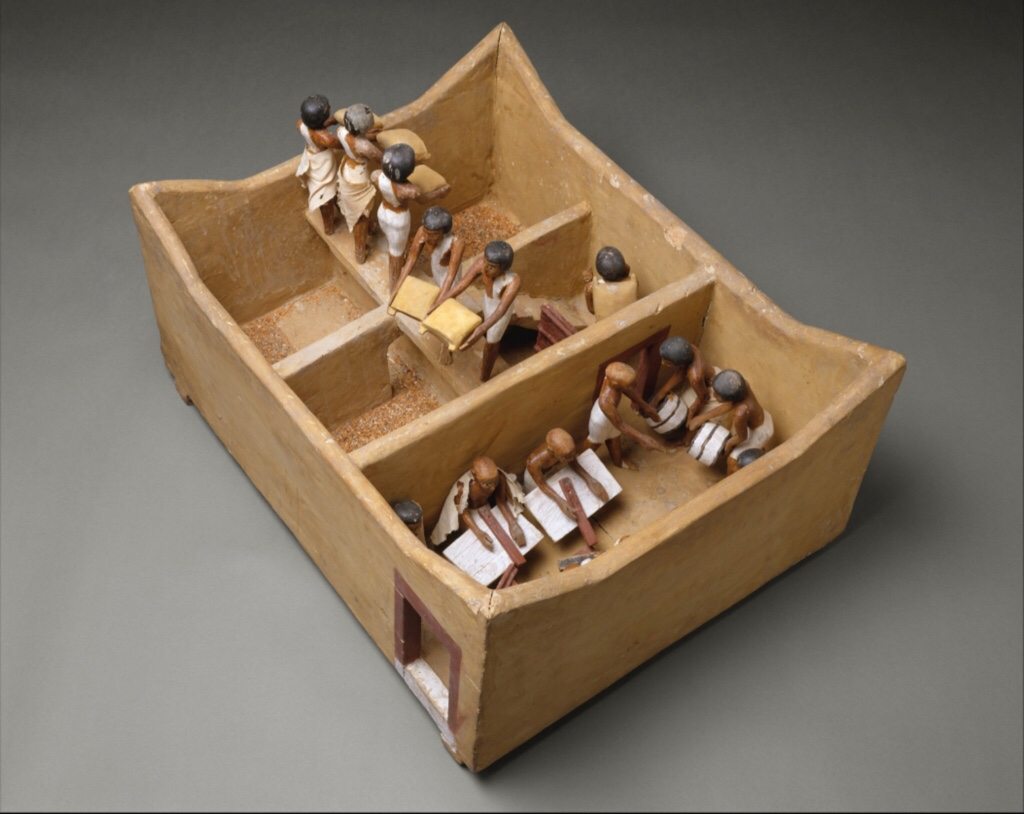

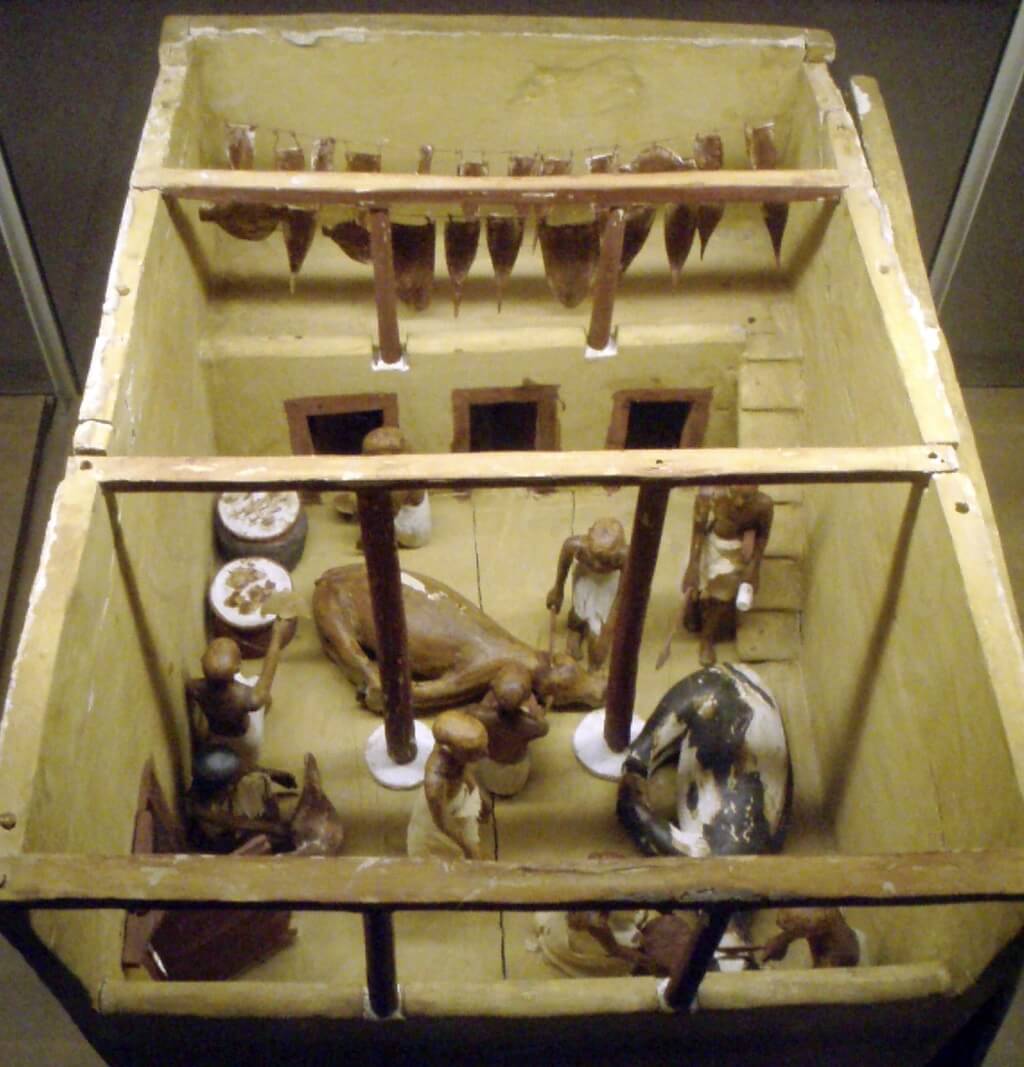

This model of a granary was discovered in a hidden chamber at the

side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the royal chief

steward Meketre, who began his career under King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep

II of Dynasty 11 and continued to serve successive kings into the early

years of Dynasty 12.The four corners of this model granary are peaked in

a manner that is sometimes still found in southern Egypt today

presumably to offer additional protection against thieves and rodents.

The interior is divided into two main sections: the granary proper,

where grain was stored, and an accounting area. Keeping track of grain

supplies was crucial in an agricultural society, and it is noteworthy

that the six men carrying sacks of grain here are outnumbered by nine

men taking care of measuring and accounting. Of the four scribes two are

using papyrus scrolls, two write on wooden writing boards.

This model of a granary was discovered in a hidden chamber at the

side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the royal chief

steward Meketre, who began his career under King Nebhepetre Mentuhotep

II of Dynasty 11 and continued to serve successive kings into the early

years of Dynasty 12.The four corners of this model granary are peaked in

a manner that is sometimes still found in southern Egypt today

presumably to offer additional protection against thieves and rodents.

The interior is divided into two main sections: the granary proper,

where grain was stored, and an accounting area. Keeping track of grain

supplies was crucial in an agricultural society, and it is noteworthy

that the six men carrying sacks of grain here are outnumbered by nine

men taking care of measuring and accounting. Of the four scribes two are

using papyrus scrolls, two write on wooden writing boards.

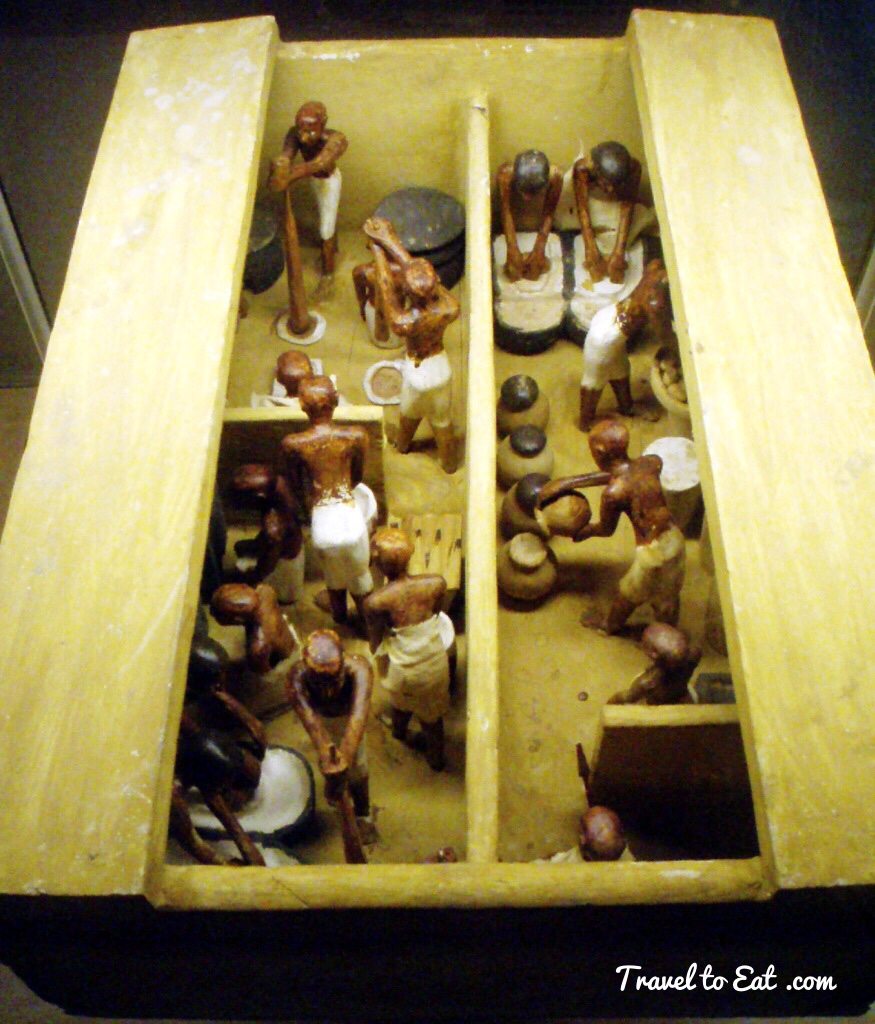

The figures in Meketre’s models, especially those from the combined

bakery and brewery, are small works of art in their own right. Although

several figures in a given model may be performing the same task, each

is a distinct individual, and each has a slightly different pose.The

most striking aspect of Meketre’s brewers is their arms, which were

specially crafted for each figure according to the task he performs.

These figures and those in Meketre’s other models convey a feeling of

motion that was seldom achieved, or desired, in more formal Egyptian

statuary. Note particularly the pose of the man decanting beer at the

right.

The figures in Meketre’s models, especially those from the combined

bakery and brewery, are small works of art in their own right. Although

several figures in a given model may be performing the same task, each

is a distinct individual, and each has a slightly different pose.The

most striking aspect of Meketre’s brewers is their arms, which were

specially crafted for each figure according to the task he performs.

These figures and those in Meketre’s other models convey a feeling of

motion that was seldom achieved, or desired, in more formal Egyptian

statuary. Note particularly the pose of the man decanting beer at the

right.

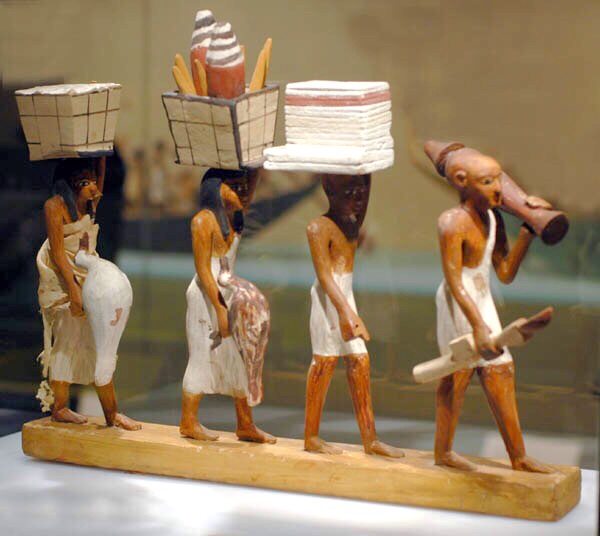

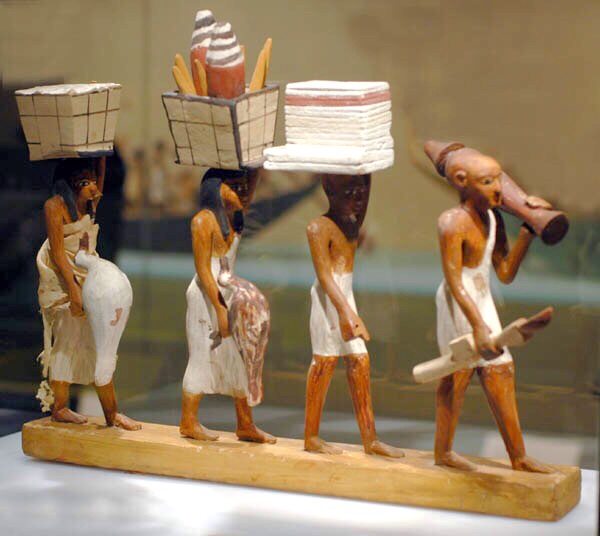

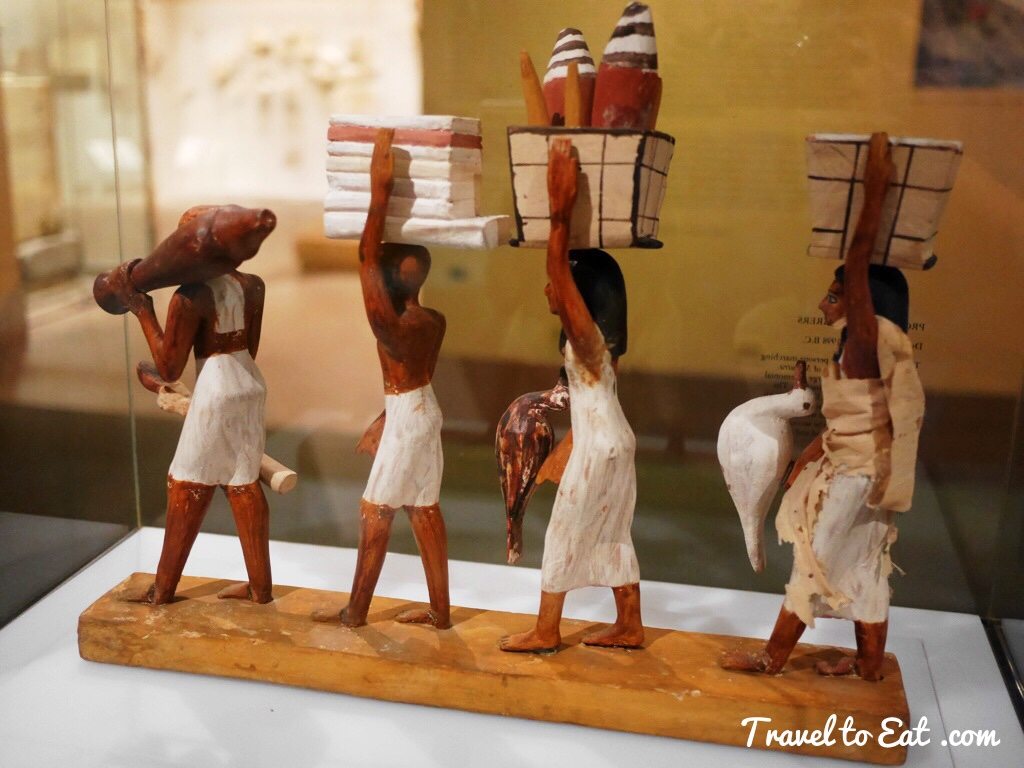

This masterpiece of Egyptian wood carving was discovered in a hidden

chamber at the side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the

royal chief steward Meketre. Together with a second, very similar

female figure (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo) this statue flanked

the group of twenty two models of gardens, workshops, boats, and a

funeral procession that were crammed into the chamber’s narrow space.

Striding forward with her left leg, the woman carries on her head a

basket filled with cuts of meat. In her right hand she holds a live duck

by its wings. The figure’s iconography is well known from reliefs of

the Old Kingdom in which rows of offering bearers were depicted. Place

names were often written beside these figures identifying them as

personifications of estates that would provide sustenance for the spirit

of the tomb owner in perpetuity. The woman is richly adorned with

jewelry and wears a dress decorated with a pattern of feathers, the kind

of garment often associated with goddesses. Thus, this figure and its

companion in Cairo may also be associated with the funerary goddesses

Isis and Nephthys who are often depicted at the foot and head of

coffins, protecting the deceased.

This masterpiece of Egyptian wood carving was discovered in a hidden

chamber at the side of the passage leading into the rock cut tomb of the

royal chief steward Meketre. Together with a second, very similar

female figure (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo) this statue flanked

the group of twenty two models of gardens, workshops, boats, and a

funeral procession that were crammed into the chamber’s narrow space.

Striding forward with her left leg, the woman carries on her head a

basket filled with cuts of meat. In her right hand she holds a live duck

by its wings. The figure’s iconography is well known from reliefs of

the Old Kingdom in which rows of offering bearers were depicted. Place

names were often written beside these figures identifying them as

personifications of estates that would provide sustenance for the spirit

of the tomb owner in perpetuity. The woman is richly adorned with

jewelry and wears a dress decorated with a pattern of feathers, the kind

of garment often associated with goddesses. Thus, this figure and its

companion in Cairo may also be associated with the funerary goddesses

Isis and Nephthys who are often depicted at the foot and head of

coffins, protecting the deceased.

While there are no glittering jewels or gold, these exquisite figures are more valuable than a whole bucket of gold. I love the little details of life four thousand years ago. In fact, Meketre may well have achieved the immortality through these little dioramas. Obviously any visit to New York deserves a visit to the Metropolitan Museum.

(translates to The Sun is my protection) in western Thebe was a high official during the reign of Mentuhotep II, Mentuhotep III, Mentuhotep IV and Amenemhat I which spanned the 11th and 12th Dynasties. He served as Overseer of the Six Great Law Courts, Treasurer and Chief Steward. He died during the early years of Amenemhat’s reign and was one of the last high-officials to be buried at Thebes before the royal court moved to Lisht. All the accessible rooms in the tomb of Meketre had been robbed and plundered during Antiquity; but early in 1920 the Museum’s excavator, Herbert Winlock, wanted to obtain an accurate floor plan of the tomb’s layout for his map of the Eleventh Dynasty necropolis at Thebes and, therefore, had his workmen clean out the accumulated debris. It was during this cleaning operation that the small hidden chamber was discovered, filled with twenty-four almost perfectly preserved models. Eventually, half of these went to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and the other half came to the Metropolitan Museum in the partition of finds.

Funeral Boat Paddling, Dynasty 12 Early Reign of Amenemhat I, 1981-1975 BC. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Funeral Boat Paddling, Dynasty 12 Early Reign of Amenemhat I, 1981-1975 BC. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Traveling Boat Rowing, Dynasty 12 Early Reign of Amenemhat I, 1981-1975 BC. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Kitchen Tender Rowing, Dynasty 12 Early Reign of Amenemhat I, 1981-1975 BC. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Traveling Boat Rowing, Dynasty 12 Early Reign of Amenemhat I, 1981-1975 BC. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Offering

Bearers, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of Amenemhat I, ca.

1981–1975 B.C. Tomb of Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

Offering

Bearers, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of Amenemhat I, ca.

1981–1975 B.C. Tomb of Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC

A

funerary model of a garden, dating the 11th dynasty, circa 2009-1998

B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of Meketre.

Metropolitan Museum, NYC. Photo Keith Schengili-Roberts

A

funerary model of a granary, dating the 11th dynasty, circa 2009-1998

B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of Meketre.

Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

A

funerary model of a granary, dating the 11th dynasty, circa 2009-1998

B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of Meketre.

Metropolitan Museum, NYC. Photo Keith Schengili-Roberts

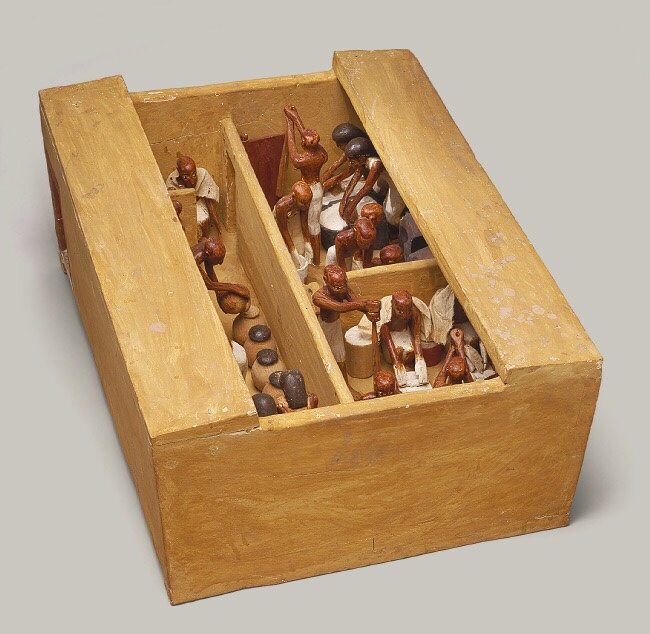

A

funerary model of a bakery and brewery, dating the 11th dynasty, circa

2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of

Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC. Photo Keith Schengili-Roberts

A

funerary model of a bakery and brewery, dating the 11th dynasty, circa

2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of

Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

Figures

from a funerary model of a bakery and brewery, dating the 11th dynasty,

circa 2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes.

Tomb of Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

Funerary

model of a bakery, dating the 11th dynasty, circa 2009-1998 B.C.

Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of Meketre. Cairo

Museum, Egypt

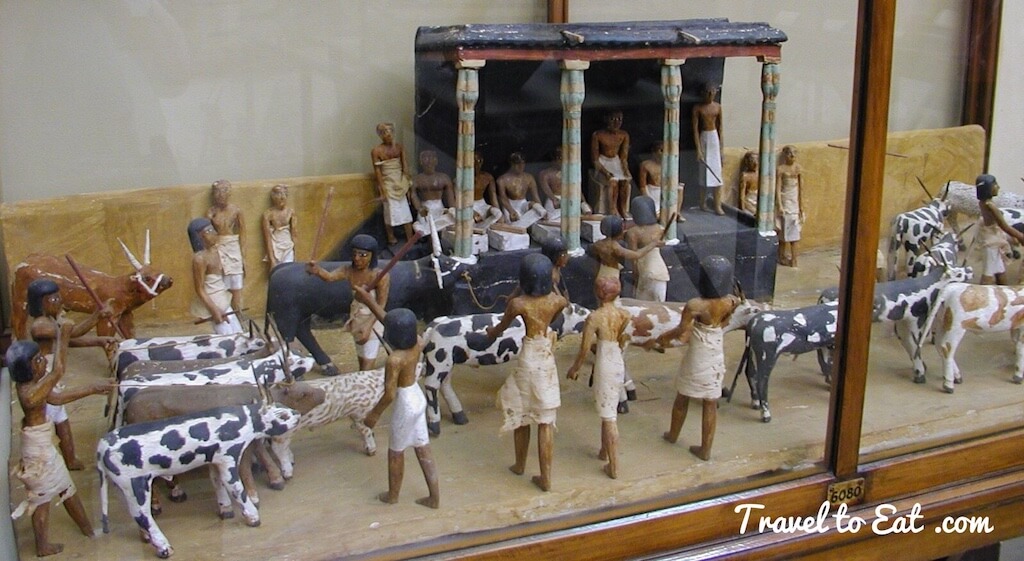

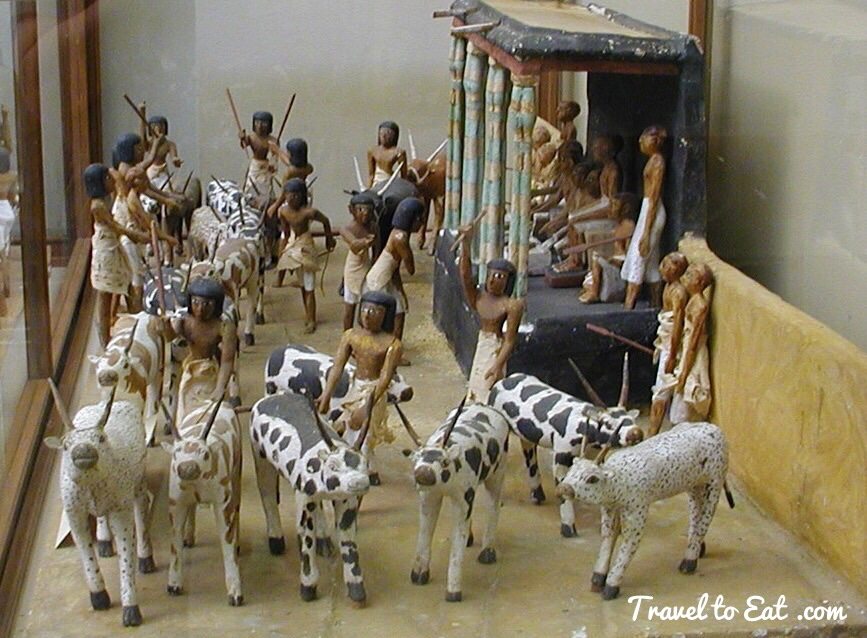

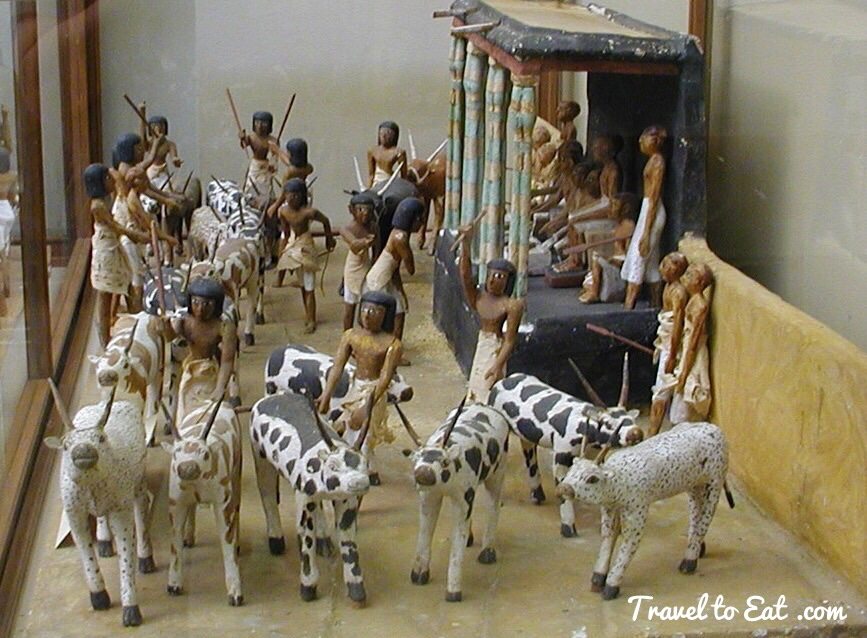

Le chancelier Méketrê surveille le comptage de son bétail Musée égyptien du Caire, Le Caire, Égypte. Photo Gérard Ducher

Le chancelier Méketrê surveille le comptage de son bétail Musée égyptien du Caire, Le Caire, Égypte. Photo Gérard Ducher

A

funerary model of a cattle stable, dating the 11th dynasty, circa

2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Photo

Keith Schengili-Roberts

A

funerary model of a slaughter house, dating the 11th dynasty, circa

2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Tomb of

Meketre. Metropolitan Museum, NYC. Photo Keith Schengili-Roberts

A

funerary model of a cloth weaving shop, dating the 11th dynasty, circa

2009-1998 B.C. Painted and gessoed wood, originally from Thebes. Cairo

Museum, Egypt

Statue

of an Offering Bearer, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of

Amenemhat I, ca. 1981–1975 BCE. Tomb of Meketre. Metropolitan Museum,

NYC

While there are no glittering jewels or gold, these exquisite figures are more valuable than a whole bucket of gold. I love the little details of life four thousand years ago. In fact, Meketre may well have achieved the immortality through these little dioramas. Obviously any visit to New York deserves a visit to the Metropolitan Museum.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق